In the summer of 1973, the cast and crew of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre were suffering through what was, by most accounts, a thoroughly miserable shoot. The heat and humidity were almost unbearable; the interior location where much of the film’s third act took place, an old farmhouse outside Round Rock, was dressed with animal bones and blood, which had begun to stink in the broiling Texas air. The stench was so bad that some crewmembers were throwing up outside between takes.

Directed by Tobe Hooper, then a largely unknown 20-something filmmaker from Austin, the film’s painfully low budget only added to the misery. Funds didn’t stretch to a wardrobe of multiple costumes, so the cast were forced to wear the same filthy outfit day after day in order to maintain continuity. Several actors, including 18-year-old John Dugan, who plays a catatonic ‘grandfather’, had to spend hours each day in stifling old-man makeup. Marilyn Burns, who played the film’s tormented ‘final girl’, had it even worse: she was forced to spend hours tied to a chair, covered in fake blood. At one pivotal moment, a special effect failed to work properly so Burns had her finger sliced open, for real, so that Dugan’s grandfather could lick the blood from the wound as the camera rolled.

By the time the wrap party took place at the end of 32 days’ filming, just about everyone involved in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was tired, sore and angry. Actor William Vail still had the fading remnants of a black eye from where Gunnar Hansen (the hulking man behind the Leatherface mask) had struck him with a prop hammer. Then there were the psychological bruises from Hooper’s exacting approach: the punishingly long days (one stretched to 18 hours or more, depending on who’s telling the story), the multiple takes, his insistence that actors Hansen and Paul A Partain (who played the wheelchair-bound Franklin) were kept away from the rest of the cast.

“Everyone hated me by the end of the production,” Hooper admitted in 2014. “It just took years for them to kind of cool off.”

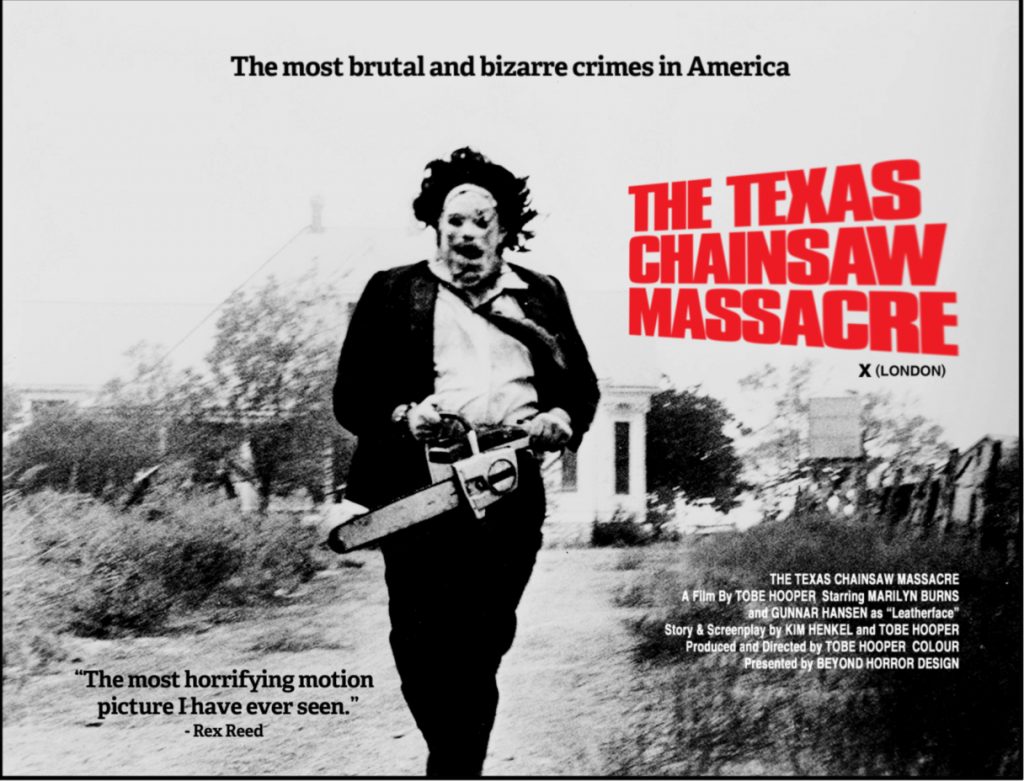

All of this for a movie that, at least in theory, should have shown at a few grindhouse theatres and drive-ins before vanishing without trace. As history now recalls, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre – or The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, as its title calls it – joined a growing club of low-budget horror movies that changed the genre forever. Even today, Texas Chainsaw is rightly mentioned in the same breath as such boundary-pushing features as Night Of The Living Dead, The Last House On The Left and Halloween.

Indeed, Texas Chainsaw is now such a horror staple that discussions surrounding it have become well-worn: the initial shock and controversy surrounding its release, particularly in the UK, where the BBFC banned it for several years. How its intensity and style influenced dozens of other filmmakers and their movies, including Ridley Scott’s Alien. Then there’s its other big talking point: how, despite the attention-grabbing title, the movie’s remarkably low on gore. Instead, Hooper uses sound, editing and framing to suggest the violence and bloodletting.

What the long-suffering cast and crew of Texas Chainsaw might not have banked on, as they drowned their sorrows at the wrap party in 1973, was just how the atmosphere of that arduous shoot would feed into the finished movie. Even if the audience doesn’t consciously notice as much, there’s a distancing level of artifice in even the goriest of horror flicks. Deep down, we know that what we’re watching actors acting and special effects dowsing and splattering across the screen; there’s a certain amount of comfort in knowing that what we’re seeing is all make believe, like a rollercoaster that simulates the terror of a maniac driving down a motorway without the accompanying danger.

In Texas Chainsaw, the barrier between the world on the screen and the viewer feels as delicate as cling film, and likely to break at any moment. It’s a car flying down a motorway without any brakes; a rollercoaster wildly out of control.

The plot is back-of-a-cigarette-packet stuff: a bunch of youngsters are driving into rural Texas, ostensibly to check on the grave of a family member; instead, they’re waylaid by stories of a spot where they can go swimming, and wind up in the locus of a terrifying family of former slaughterhouse workers, who hunt and murder them one by one. Texas Chainsaw came four years before the slasher genre properly erupted with the advent of John Carpenter’s Halloween, and it’s worth noting how Hooper’s film differs from the conventions we’d later see in the dozens of copycat slashers that followed in Carpenter’s wake.

There’s little of the high school, soap opera relationship back-and-forth between the characters. Hooper doesn’t make the same links between partying, libidinous youths and violent death that later movies would later create. The disabled, difficult and ultimately doomed Franklin is an unusual kind of character to see in a horror film of its vintage. Most interestingly of all, Hooper doesn’t give the audience the release of a final confrontation between heroine and villain – the closest we get is when the hitcher played by Edwin Neal is run over by a truck. The terrifying Leatherface and the rest of the cannibal family go otherwise unpunished at the end of the movie; the luckless Sally (Burns) escapes with her life, but not, we suspect, her sanity.

Instead, Texas Chainsaw offers approximately 80 minutes of largely unbroken, unvarnished fear and loathing: a film that drags horror into the turbulent present of 70s America, with its Vietnam war anger, Watergate scandal and fuel shortages. It’s a raw, ugly film for a raw and ugly era. As much by serendipity as design, Texas Chainsaw’s lack of budget (originally set at a tiny $60,000, but swelling to somewhere nearer the $300,000 mark during editing) is key to that rawness.

The sense of death positively emanates from Hooper’s movie; the sculptures made from bones and (fake, thankfully) dried skin created by production designer Robert A Burns sell the reality of the homestead run by several generations of unhinged cannibals. Hooper’s frenzied direction and Daniel Pearl’s inventive cinematography create an air of aggression and horror that gallons of blood and severed prosthetic limbs never could. Some of the key sequences in Texas Chainsaw are created through simple filmmaking techniques rather than special effects: the moment when William Vail’s character is attacked by the masked leatherface is achieved through the toe curling sound – the thud and sickening squelch of the hammer hitting a human skull – some great physical acting (Vail twitching his legs as he lies on the floor, Gunnar Hansen throwing the actor into a room off-screen), and finally, the final wrench of a metal door blocking the scene from view.

The similarly terrifying moment where Leatherface lifts the screaming Pam (Teri McMinn) into the air and mounts her on a meathook is another example of filmmaking ingenuity winning out over effects. Hooper had initially thought about having the hook exit a prosthetic neck, with an accompanying geyser of blood; the lack of budget – and Hooper’s ill-fated desire to get the film a PG-rating – quickly nixed that idea. Instead, McMinn was hung on a simple and very uncomfortable saddle; the screaming and Pearl’s low camera angle effortlessly sell the scene’s horror.

It’s often said that Hooper never made another film with the impact of Texas Chainsaw, and that may be in part because it’s so hand-made. A lot of the editing took place in Hooper’s own house. The director couldn’t afford to commission an expensive soundtrack, so he Wayne Bell made it themselves – a nerve-jangling cacophony of exotic instruments and unearthly noises and screams. Lacking a decent budget to fall back on, Hooper instead leaned on the experimental, freaky approach to filmmaking he employed in his earlier shorts – and his little-seen feature, the self-described “hippie movie”, Eggshells. The higher up the filmmaking food chain Hooper went, the more he lost sight of the sticky tape-and-knotted-string invention of Texas Chainsaw – though as anyone who’s the unforgettable Lifeforce will tell you, he never quite lost his eccentric sensibility.

Then again, modern filmmaking – and horror in particular – often mislays the grubby quality that came so readily to the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Hooper’s 1986 sequel was gorier, but dialled up the black comedy that merely crawled under the surface of the original. The other movies in the franchise are largely forgettable, precisely because they can’t capture the lightning-in-a-bottle atmosphere that Hooper captured way back in the summer of 1973. John Landis once joked that the remake of Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which came out in 2003, resembled a shampoo commercial – a quip that unwittingly sums up the difference between Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw and most other horror movies.

The heat; the stench and decay; the feeling of imminent violence: these are things that have a tendency to be lost in most genre films. Haunted house movies and glossy slasher flicks are, in essence, fun ghost train rides. There’s a distance between us and the movie that makes for entertainment rather than something truly disturbing. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre cuts through that distance. We can almost smell the engine oil emanating from Leatherface’s chainsaw. We can almost feel his breath in our face. Over 40 years later, the breath still feels hot and rancid.