NB: The following contains spoilers for The Thing.

Critically mauled on release and largely overlooked in cinemas, John Carpenter’s The Thing has only grown in stature since 1982. What were once condemned as deficiencies – its graphic gore and violence, icy tone and low-key characterisation – are now generally regarded as positives. Its simple story about a group of scientists and misfits who encounter a shape-shifting alien in their Antarctic outpost, The Thing has aged remarkably well for a 35-year-old film: Rob Bottin’s practical effects are still extraordinarily imaginative, and fans still debate the finer points of its action today. Who sabotaged the fridge full of blood samples? Where MacReady and Childs still human at the end?

Behind the scenes, the story of how The Thing was made is a fascinating one all by itself. Originally a novella, Who Goes There?, written by John W Campbell Jr, The Thing was originally adapted in 1951 as The Thing From Another World, a hackle-raising thriller that dropped Campbell’s idea of a creature capable of imitating its host and replacing it with a hulking man-monster played by James Arness. As written by Bill (son of Burt) Lancaster, Carpenter’s The Thing went right back to the source, delivering a tense whodunnit where it’s not always clear who’s the alien. In his adaptation, Lancaster whittled down the base’s inhabitants from 37 to 12, allowing him more time to establish his ensemble cast, among them gruff helicopter pilot MacReady (Kurt Russell), veteran scientist Blair (Wilford Brimley) and pothead conspiracy theorist Palmer (David Clennon).

John Carpenter’s first studio film, garnered off the back of indie hits such as Halloween and The Fog, The Thing was a complex production, even with the handsome budget given over by Universal. Many of Rob Bottin’s VFX ideas were new and untested; location filming in British Columbia was freezing cold, while the shoot on LA sound stages saw actors spend hours on a refrigerated set in the midst of a searing hot summer. Through the process of making The Thing, there were all kinds of creative roads not travelled, scenes that were shot but later deleted. Some of the latter exist on The Thing’s DVD and Blu-rays, and are largely alternate or longer takes of existing sequences, like the moment where Blair dissects a dead chunk of alien and ruminates on its protean abilities.

The deleted scenes we’re concentrating on here are more pivotal, and would have changed the trajectory of the film quite substantially. Although it’s not a comprehensive list, it gives an idea of how The Thing could have shape-shifted into a whole other form…

MacReady’s blow-up doll

A ribbon of bleak humour runs through The Thing, and even its most violent sequences have a kind of EC Comics, grand guignol quality to them. One planned scene would’ve provided an odd flash of levity early on – and a jump-scare pay-off later in the story. As originally written by Bill Lancaster, the otherwise solitary MacReady would have shared his room with an unlikely companion: a blow-up doll. The script describes a scene where MacReady, watching some VHS tapes retrieved from a doomed Norwegian camp, absent-mindedly blows up what at first appears to be a balloon. As Lancaster writes:

“Bleary-eyed, MacReady is in the process of blowing up some strange inflatable object. As he puffs away, he still keeps an eye on the Norwegian video tapes. His balloon begins to take shape. It blossoms into a life-size replica of a full-breasted woman. Something on the tape catches his eye. He rewinds, then starts it forward again.”

It’s an incidental moment, and one that likely would have been forgotten as the Thing starts killing off the cast. Later, however, the doll makes a surprise reappearance as Nauls (TK Carter) pokes around a darkened room with a roof left damaged by the monster’s off-screen antics:

Nauls kicks over a chair. A naked, fleshy object bounds high into the air. Nauls thrusts out his torch, catching the breasts of the inflatable woman. She pops and is sucked out through the hole in the roof. Nauls tries to catch his breath.

NAULS: Goddamn white women.

It appears that this sequence survived into the shoot itself, since set photos of MacReady blowing up the doll can still be found on the web. It’s not clear, exactly, why the idea was dropped; it’s possible that, in a film with an all-male cast, the doll might have seemed like a filmmaker thumbing his nose at an audience wondering where all the real women have gone. Or, alternatively, Carpenter may have decided it was more of a distraction from the story rather than a help.

Unfortunately, we may never know whether the resulting jump-scare would have worked or not. To date, none of the deleted scenes involving the doll have ever emerged.

Bennings gets it in the neck

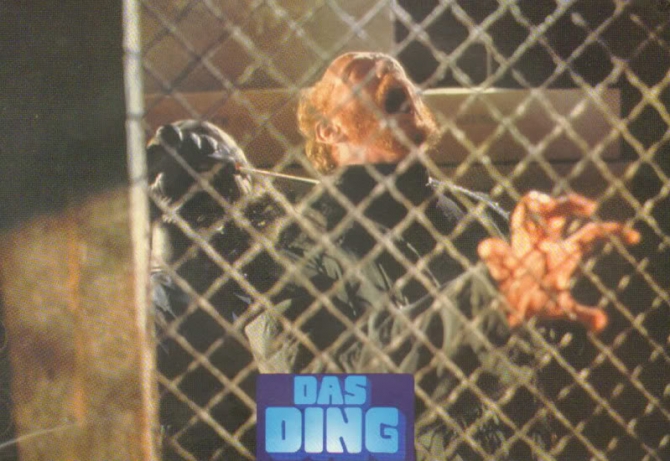

One of The Thing’s most chilling scenes didn’t even exist in the shooting script. In the finished movie, Bennings (Peter Maloney) is killed in a storeroom and later seen running out into the Antarctic night. Surrounded by his comrades and lit by the sickly glow of a flare, we see that the Thing is still in the process of imitating its latest victim: Bennings’ hands are gnarled and unearthly; cornered, he lets out a blood-curdling roar.

Originally, Bennings would’ve followed a noise into the kennel – the site of all the pandemonium with the dogs earlier on – where he’s attacked from behind by an unseen assailant, who promptly stabs him in the neck. The parts of this sequence, where Bennings very (very) slowly makes his way to the kennels, still exists, but his death seems to be lost. Like the blow-up doll scene above, the only evidence we have that it was even shot are a series of still set photographs. Even here, it’s impossible to work out who it is that’s doing the stabbing.

Carpenter changed Bennings’ fate during The Thing‘s reshoots, and it’s fair to say that what we got in the end is far more effective than the slasher movie-type death originally envisaged. Interestingly, Bill Lancaster’s script imagined a death for Bennings that was, presumably, too expensive to use: while following a pair of escaped dogs, he’s pulled through a sheet of ice by the Thing’s grabbing arms.

Shovel attack

For a film so famous for its imaginative death scenes, it’s interesting to note how many characters actually die off-camera. Take Fuchs, for example: in the finished film, he seems to be another character who just vanishes. We see him go outside with a flare having seen a shadow walk past his room; he finds the tattered clothing marked “MacReady”, and then that’s the last time we see him alive. His burned body is found in the snow, barely recognisable. (“Is it Fuchs?”) Apparently burned himself rather than be absorbed by the Thing.

Although Fuchs was always intended to die off-screen, the method of his demise would have been rather different, according to Lancaster’s script. While hunting through the chilly facility, Childs and Palmer would have discovered Fuchs pinned to a door with an axe. Once again, the sequence was evidently shot, as production photos of actor Joel Polis, an implement – scripted as an axe, but actually a shovel in the film – sticking out of his chest, can still be found.

What Carpenter went for in the end was rather more ambiguous. It’s suggested Fuchs set himself on fire with a flare rather than be absorbed by the Thing; is that the case, or did the Thing destroy him because it didn’t have time to imitate his form? It’s one of the film’s lingering mysteries.

Nauls’ fate

One of The Thing’s most colouful, likeable characters is surely Nauls – the rollerskating, fast-talking cook played by TK Carter. Maybe it’s for the best, then, that his departure from the film is quiet and relatively dignified: as MacReady’s laying an explosive trap for the monster, Nauls hears a noise in the dark, heads towards it, and promptly vanishes for good.

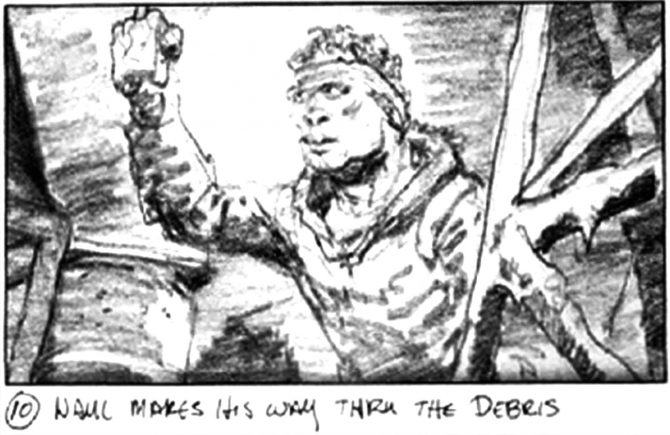

We never see how Nauls actually died – in fact, we’re just assuming that he did – but a death scene was originally written and storyboarded. In a rare sequence of drawings (which can be found on YouTube) Nauls sees the twitching body of Garry (Donald Moffat) before he’s grabbed by the Thing, which still looks like Blair. Later, we see Nauls, partly assimilated by the monster, come bursting up through the floor in front of MacReady before the final confrontation. “Help me,” Nauls cries, as tentacles and other unholy things come writhing from his mouth.

It would have been as horrific a transformation sequence as any of the others in The Thing, but it seems there simply wasn’t the time or budget to stage it. Rob Bottin was already spending so long in his workshop that he made himself ill – coming up with the effects for a tortured Nauls was clearly too much to get finished in the time left. Instead, we’re left with that eerie shot of Nauls simply walking off to his doom.

Also cut from the final film were a few long shots of the Blair monster just before it’s blown to smithereens: these were brought to life using stop-motion, and they’re quite endearing in their own way. Carpenter and his collaborators, figuring that the jerkiness of the animation didn’t match the rest of the movie, decided the conclusion was better without them. Instead, the Blair monster is largely shown in glorious close-up.

Unhappy endings

For a mainstream studio movie, The Thing’s ending is bravely downbeat. Our two survivors, MacReady and Childs, sit in the embers of a destroyed camp, fully aware that, once the fires go out, they’ll freeze to death long before help will arrive. As great as it is, a certain amount of nervousness lingered around such a depressing conclusion, and Carpenter even shot an epilogue as an “insurance policy”: a much later scene where MacReady’s shown recovering at another research station, a quick blood test revealing that he’s human.

Fortunately, this was never used, though some TV versions of the movie did add another postscript that offered far less comfort: the Thing, disguised as a dog, running from the smoking remains of Outpost 31. It’s not a bad idea, since it brings the story full-circle, though the horribly cheesy voice-over (“Who knows what evil lurks in the skies…”) is something of an acquired taste.

Ultimately, the cut Carpenter went with – MacReady, Childs, the dying fires – feels like the perfect end for a frosty horror classic.