This feature contains spoilers for Big Fish.

“Have you ever heard a joke so many times you’ve forgotten why it’s funny? And then you hear it again and suddenly it’s new. You remember why you loved it in the first place.”

In the last two decades of Tim Burton’s filmography, Big Fish feels like something of an outlier. Chronologically, it slots in between his ‘reimaginings’ of Planet Of The Apes and Charlie And The Chocolate Factory, both of which are much more typical of his 21st century output. This film isn’t worlds apart from his usual style, but for once, it’s the substance of the story that connects with his sensibilities as a storyteller.

Based on Daniel Wallace’s book Big Fish: A Novel Of Mythic Proportions, the film follows the life of Edward Bloom, an extraordinary young man (Ewan McGregor) who grows into an extraordinary old man (Albert Finney), who delights in telling extraordinary stories about his escapades. His son Will (Billy Crudup) is the only one who seems immune to his charm, and as his father reaches the end of his days, he becomes obsessed with finding out the truth behind the stories.

John August’s hugely quotable script takes the unusual structure of the novel and adapts it into a time-hopping series of vignettes that gradually paints a picture of the relationship between father and son by reconciling their clashing perspectives.

15 years on, it’s still interesting to look back on how the film converts the themes of fatherhood and the importance of storytelling into a visual medium. Burton has no shortage of fans, but the accessible quality of this understated masterpiece shouldn’t be ovelooked next to his more idiosyncratic fare. In Big Fish, the combination of August’s masterful plot structuring and Burton’s directorial sensibilities yields an interesting view of its characters past, present, and future.

Introduction

“Is this a tall tale?”

“Well, it’s not a short one…”

Early on in the film, we’re shown Edward Bloom’s birth, or his version of it anyway. In characteristically preposterous fashion, the new-born baby shoots right out of his mum and slides down a hospital corridor, sending doctors and visitors sprawling in his wake. Although Wallace’s novel was destined for adaptation before it was even published, its delivery was similarly unusual.

August read the manuscript six months before publication, and got Columbia Pictures to option the rights for him. With its adventurous emotional core and unusual structure, the resulting script attracted the attention of none other than Steven Spielberg, who wanted to make the film after he finished Minority Report, with Jack Nicholson playing the role of Edward Bloom.

Dad issues are a big recurring theme through Spielberg’s work, so this probably would have been right in his wheelhouse. However, his notes to August were to give the senior Edward more to do to make it more of a star vehicle for Nicholson. A few script drafts later, Spielberg’s attention was captured by Catch Me If You Can instead, and he reportedly admitted to the producers that he’d been off the mark in changing the script.

The script came to Burton, and in the main, he’s definitely the better choice. When someone figures out a VPN for parallel universe versions of Netflix, the Spielberg-Nicholson version will probably be worth a watch, but what makes the film itself such a masterpiece is the match of a different director’s sensibilities with a Spielberg-level project.

He nails the Southern Gothic tone and there’s plenty of opportunity to enjoy himself with macabre characters – because of course Danny DeVito turns out to have been a werewolf the whole time. But what’s really unusual about this is that both the director and the screenwriter lost their fathers before coming to this particular project.

August was first attracted to the project because he saw something of himself in Will, having trained as a journalist and not known as much about his father as he’d like, whereas Burton had sadly lost both of his parents in almost as many years. Even if it is based on a pre-existing story, there’s an in-built catharsis to these two creative forces coming together to tell this particular story of a man looking for his dad.

The past

“Kept in a small bowl, the goldfish will remain small. With more space, the fish will double, triple, or quadruple its size.”

All of Big Fish‘s tall tales are glorious. Much of the film takes place through the senior Edward’s stories about his adventures, and every single new development is funny, surprising, and delightful to watch. McGregor and Finney are both affecting an Alabama accent for this, and somehow, they’re perfectly matched as the same character at different ends of his life.

As Will shakes his head in the present day, we’re as beguiled as everybody else in the story by his tales of witches, giants, secret towns, and all the other escapades he had. It’s not until later that we come to grasp why Will hates these stories, and as pure magical realism, they’re really entertaining to watch.

The film has a lot of fun playing with Edward’s unreliability as a narrator for laughs too. As a boy, he and his classmates look into a witch’s eye and see a vision of how they’re going to die. Then at one point when the older Edward gets lost in an apparently haunted forest, with trees wrapping their branches around him, he simply proclaims “Wait, this isn’t how I die” at the exact moment that the narrator reminds him, and with one bound, he’s free.

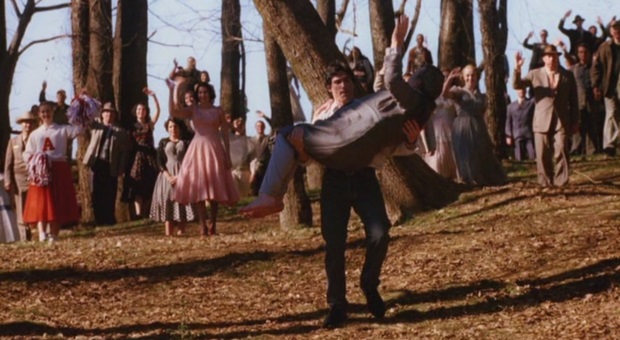

The next such moment is memorable for other reasons, as Edward plays on the old cliché that time stops when you first meet the love of your life. Cue an iconic slow-motion scene as Edward crosses a circus ring to try and reach his future wife, Sandra, that’s quickly punctured when he adds “the thing they don’t tell you, is that once time starts again, it moves extra fast to catch up.” Sandra eludes him because the film around him speeds up while he remains at regular speed.

It’s a wonderful visual trick, but what’s interesting about the passage that follows is that the fantasy gets dialled down a bit. It’s still very, very romantic, but there’s not so much fantasy to Edward’s determined wooing of Sandra. By the same token, we’re reminded that it’s still very much one storyteller’s perspective, as Sandra’s current boyfriend Don gets pretty short shrift in the grand scheme of things.

We’re inclined to believe Edward’s stories about the life he has led, but his description of himself as a big fish in a small pond, comparing himself to a legendary uncatchable Beast in the parable he tells from Will’s childhood right up to his wedding day, points to the motivation behind his son’s bitterness. From the very beginning of the film, the trips to the past also count earlier memories of Edward telling Will his stories, and growing ever more exasperated as he grows into adulthood.

The present

“You spend years trying to corrupt and mislead this child, fill his head with nonsense, and still it turns out perfectly fine.”

On his wedding night, Will has a falling-out with Edward over the umpteenth telling of his story about the Beast. The tale of fighting a giant catfish that ate his wedding ring is his head-canon reason for missing his son’s birth. Will sees this as a bit of a wind-up, and they barely talk until three years later, when we find Edward stricken by terminal cancer.

To Will’s annoyance, his wife Joséphine (Marion Cotillard) is utterly charmed by Edward. She’s expecting their first child, and the fact that he’s about to become a father himself clearly motivates his arc. While comparing his dad to an iceberg (which immediately provokes an anecdote about the time he saw a mammoth frozen inside one in Texas), he inadvertently hurts his feelings by accusing him of not being himself.

If Edward’s side of the story is Forrest Gump, Will’s is Citizen Kane. He’s a journalist, and while his father bemoans his son going into a storytelling profession that focuses on facts and leaves out “the interesting parts”, we see those instincts at work as he tries to find out what was really going on with this unknowable figure in his life.

When the flashbacks catch up with Will’s birth, the story flips to his perspective for a while, as he looks into his father’s time as a travelling salesman (another iteration of the fish who’s always on the move), when he built a trust to save the mythical town of Spectre from ruin. He goes out there himself and meets Jenny (Helena Bonham Carter), his father’s fellow trustee.

In Will’s mind, the absence of his father has led to him speculating that he must have cheated on his mother. For a while, that bias seems to colour his search for the truth. Resenting the fact that his dad was on the road has led him to imagine the worst of him, and he hopes to get some answers from Jenny.

The truth turns out to be more banal, but the reveal of Bonham Carter’s dual role in the film as the witch from back when Edward was a boy literally brings the story around full circle. Will says that logically she couldn’t have been the witch, because the timing doesn’t work out, but Jenny counters that there are only two women in Edward’s life – Sandra “and everyone else”. Once again, it’s a canny bit of visual storytelling that marks the cleverness of the adaptation.

Will returns home to find his father’s condition has worsened, which is when he finally learns the story of the day he was born. As the family doctor (Robert Guillaume) tells him, if it’s a choice between missing the birth because he was on the road, trying to make money for his family back in the days when he wouldn’t have been allowed in the delivery room anyway, or the tall tale, maybe the tall tale is preferable.

The future

“A man tells his stories so many times that he becomes the stories. They live on after him, and in that way he becomes immortal.”

As the film reaches its climax, we learn the only story that Edward never told was the story of his own death; the vision he saw in the witch’s eye. He claims he wouldn’t like to spoil the ending, but the emotional crux of the story comes as he asks Will to tell him the story himself.

Won over at last, Will spins a yarn about the two of them breaking out of hospital, meeting lots of the other characters on their way down to the river. Once in the water, Edward literally becomes “a really big fish” and swims away for good. Smiling, he passes away peacefully in bed. Spielberg couldn’t have done it better.

This final sequence is simultaneously joyous and tear-jerking, and finally comes around to reconciling the duelling perspectives of father and son. It’s matched only by the funeral that follows, where Will meets many of the people his father described in person for the first time.

Once again, we see that some of them aren’t exactly as advertised in the stories, but Will gets the catharsis he was looking for. We’re afforded a glimpse of him telling his own son the same stories in the future, and another circle closes as the film comes to an end.

Burton has rarely matched this fulsome mix of quirkiness and emotion in his work since, and it’s remarkable how understated the use of special effects is in this film next to pretty much everything else he’s made. In the near future, he’ll return to the trend of live-action Disney remakes that was kicked off by his Alice In Wonderland, with next year’s Dumbo, which coincidentally features Danny DeVito as a circus ringmaster once again.

With 2014’s Big Eyes representing another departure, maybe we can figure out how to detect a big palate cleanser every once in a while. Elsewhere, August’s relationship with this story continued when he wrote the book for the musical adaptation of Big Fish, which debuted on Broadway in 2013, and came to the West End in 2017. The strength of his screen adaptation should be enough to get you interested in how he’s translated it once again for the stage.

If Big Fish were only the quotable, entertaining Southern Gothic trifle that Edward tells, it would be one thing, but it’s the way in which it uses cinematic devices to adapt a story about storytelling that makes it an underappreciated modern classic.