The film: Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) is accused of murdering his wife and her lover. Despite protesting his innocence, the jury is unconvinced and he is given two life sentences, the duration of which will be endured at Shawshank Prison. There, he meets Red (Morgan Freeman) who narrates their story. The two men form a close friendship as Andy gets used to prison life, dealing with aggressive fellow inmates, corrupt prison officials, and eventually running the Shawshank library.

Frank Darabont is listed as one of the few directors who really manages to capture the work of Stephen King on screen. The Shawshank Redemption was his first major feature, but his relationship with King’s works started as one of the famous ‘Dollar Babies’, directing a short adaptation of Night Shift’s The Woman In The Room. With a few more credits to his name, Darabont went back to King to buy the rights to Rita Hayworth And The Shawshank Redemption. The screenplay eventually found its way to Rob Reiner’s Castle Rock production company and after a quick tussle over who would direct the film, Darabont found himself with a feature directorial debut.

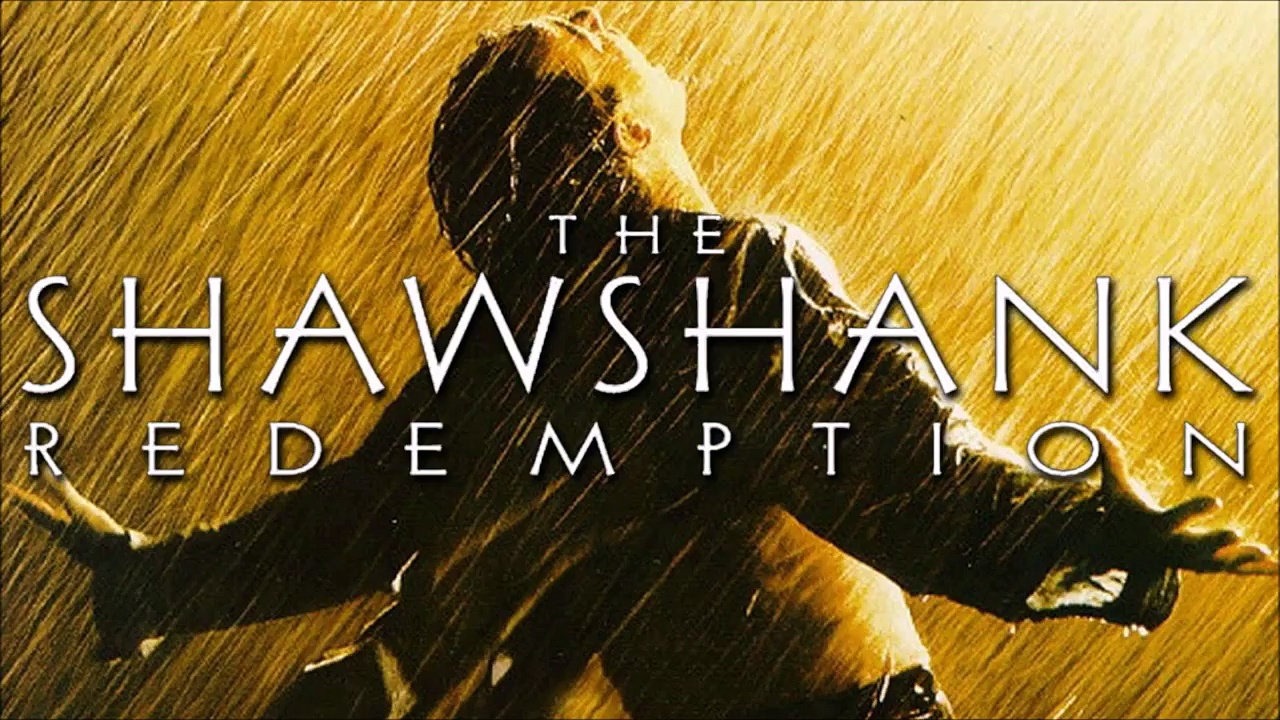

Now, The Shawshank Redemption is regarded as one of the best King adaptations there is, and has only seemed to grow in reputation over years. It is, after all, the film that launched a thousand wishes to get Morgan Freeman to narrate your life. As of the time of writing, it’s still sitting pretty atop the IMDB Top 250 chart, ahead of The Godfather. Though it’s not one of the King films I’ve ever warmed to (sacrilege in some circles, I know), it is one that I’ve grown to appreciate. It’s easy to understand why its message of hope resonates with people and how a triumph over adversity can feel so uplifting.

The major factor in this is the astonishing cast that Darabont assembled. Names such as Tom Cruise and Harrison Ford were thrown around to take on the roles of Andy and Red respectively, but now, it’s hard to imagine anyone but Robbins or Freeman in those roles. Robbins finds the steely reserve that Andy mines to survive, but with just enough ambiguity to make you wonder whether he’ll make it through his time at Shawshank. Freeman oozes charisma as Shawshank’s go to guy for anything you need, yet there’s a vulnerability to Red, particularly in the later years, that tugs on the heartstrings without becoming sentimental.

It also helps that the film has an ageless quality to it. Roger Deakins’ sepia-tinged cinematography navigates between warm and cold tones as Andy’s life in Shawshank develops, aiding the atmosphere as much as the cast. When it comes to Red’s journey post-Shawshank, the slowly-building glow of the sunshine feels almost as liberating as seeing environments outside of the prison. Darabont and Deakins reportedly didn’t always see eye-to-eye on set, but between them, they put together iconic imagery for King’s prison narrative.

Rita Hayworth And The Shawshank Redemption was part of King’s Different Seasons collection, a set of four novellas in which the author experimented outside of the horror genre. Its subtitle is ‘Hope Springs Eternal’ which would form the key theme of Andy Dufresne’s story. Hope in King works is always an elusive thing, a small light to which characters cling in the darkest moments of their stories. It’s a theme that clearly resonates with Darabont too, as his future adaptations of The Green Mile and The Mist would also explore it in different ways. Here, it’s just about the only thing that keeps Andy going and, in contrast, the thing that other characters lose.

That’s where Darabont finds the horror in King’s non-genre story. When Brooks (a wonderful James Whitmore) steps back out into the world after fifty years in prison, it’s as if he’s been transported into the future. Outside is a world of automobiles and fast-paced living that he’s unable to cope with. He’s too old, his hands are too arthritic, and he simply doesn’t understand how everything works anymore. The slow-dawning dread over the course of this sequence, that Brooks doesn’t know how to keep on in this new world, is a horrible feeling.

It’s a change from the original story, in which Brooks dies in a retirement home, but it’s an important one for Darabont to make. After everything he goes through from the Sisters’ assaults to the corruption of the Warden, the thing Andy doesn’t lose is hope. It’s the thing that helps him tunnel through rock and crawl through 500 yards of sewer. It’s what he passes on to Red, who briefly looks as if he’ll give up too. And I think that’s why The Shawshank Redemption continues to resonate so widely today. People need a letter from Andy Dufresne once in while to let them know to make it a little further, that they can take another step. To, as the great man says, get busy living…

Scariest moment: Though not an outright horror story, there are a few moments here that qualify. Andy’s first encounter with the Sisters is one of them, but there’s also a real existential fear in Red’s ongoing arc that is so mournfully chilling. Freeman captures it beautifully, that gnawing sense that Shawshank is going to be the only part of the world he sees for the rest of his life.

Musicality: Arguably one the most iconic uses of music in the oeuvre of Stephen King adaptations, the scene in which Andy plays the Letter Duet from Mozart’s The Marriage Of Figaro is a perfect moment of rebellion. In close second, it is William Sadler’s gleeful crooning to Hank Williams, replete with the kind of expressions you didn’t know a human face could pull.

A King thing: Shawshank Prison. One of the fixed spots in King’s Maine landscape, it has had several inmates over the years, including Ace Merrill of The Body and Steven Bishoff Dubay of It. The prison is referenced several times in his other works and for the eagle-eyed readers, there’s also a mention of it in Joe Hill’s NOS4R2.

Join me next time, Constant Reader, for an encounter with The Mangler.