In the realm of videogames at least, the 1980s was a comparatively sunny period: it was the era that gave us bright and cheerful classics like Super Mario Bros, Bubble Bobble and Monty Mole. Yet beneath that pleasant exterior stirred something darker and much, much nastier. Just ask Namco.

Thirty years ago, Namco was best known for the zip and vim of its arcade games; it conquered the world with Pac-Man, the first videogame to introduce a cartoon-character hero and a subsequent storm of merchandising. Before and after, Namco turned alien extermination into a colourful pastime with games like Galaxian and Galaga; it turned the apprehension of burglars into a slapstick platformer with Mappy, and made driving like a maniac look oddly adorable in Rally X.

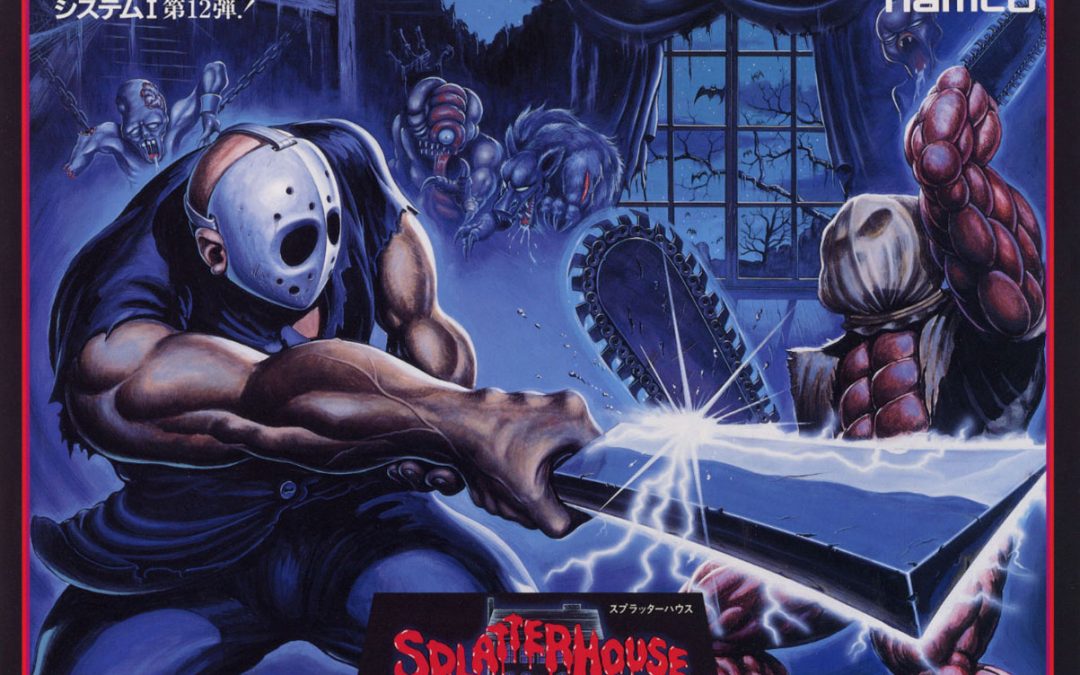

Again, though, something evil was stirring within Namco, just waiting to be unleashed. In late 1988, that day finally came with the release of Splatterhouse – an arcade machine completely unlike anything the Japanese firm had made before. Inspired by western horror games, it was a scrolling beat-em-up, not unlike hits from rival companies: Kung Fu Master, Vigilante and Double Dragon. But unlike most other games, Splatterhouse was fantastically, outlandishly gory.

If you’d stumbled on Splatterhouse in an amusement arcade in the late 80s, you would’ve immediately noted how different it looked from other videogames of the era. While games had been growing in graphical richness and violence for a while – Operation Wolf was a gun-crazed money-spinner for Taito in 1986 – none were quite as gratuitous as Splatterhouse. Cast in the role of the hockey mask-wearing anti-hero, Rick, the player stalked the halls of the title mansion, a haunted pile stuffed to the rafters with grotesque monsters and ghouls.

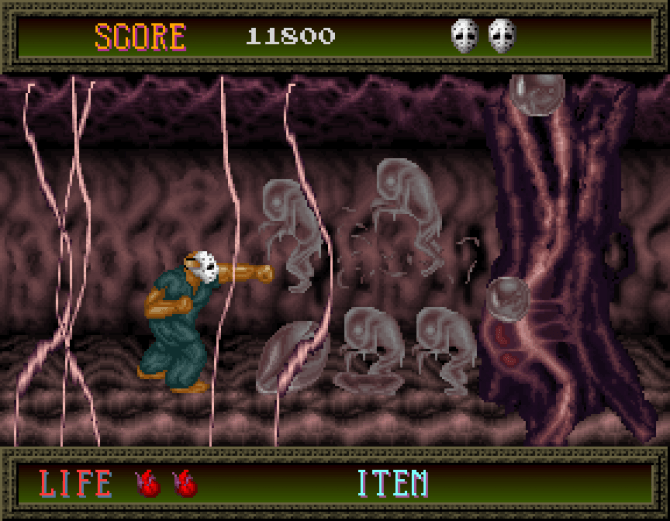

Armed at first with nothing more than his fists and feet, Rick embarked on a revenge mission against the undead who’d both murdered him at the start of the game and then kidnapped his girlfriend, Jennifer. In terms of its scenario, it wasn’t unlike Capcom’s Ghosts ‘N Goblins from 1986, but in execution, Splatterhouse was completely different: punching zombies in the face reduced them to a groaning heap of bones and green goo; picking up a weapon like a meat cleaver or a slab of wood saw enemies smashed against the wall in a bloody mess or chopped into hunks of meat.

Admittedly, the style was still cartoony, much like Ghosts ‘N Goblins was, but the larger-than-life violence and sprays of claret made it feel more like something out of EC Comics, the infamous American publisher whose output was considered so corrupting that it hastened the birth of the Comics Code.

Like EC’s comics, Splatterhouse showed a voluminous – and perhaps opportunistic – knowledge of contemporary horror. Anyone with a passing interest in pop culture would have recognised that Rick’s mask was ‘inspired’ by the hockey mask worn by Jason Voorhees in the latter Friday The 13th movies; other details in Splatterhouse were evidently borrowed from such classics as Poltergeist, The Evil Dead, Night Of The Living Dead, David Cronenberg’s The Fly, and lots more besides.

Splatterhouse was, in short, one of the first true B-movie arcade games, and its creative swiping of other storytellers’ ideas was, like any B-picture worth its salt, done with little care for self-censorship or good taste. One level saw Rick fight a gigantic, monstrous womb; once defeated, a nauseating gush of fluid issued forth. Another end-of-level boss took the form of a huge inverted crucifix. With Splatterhouse, it seemed as though Namco had intentionally set out to make a game that would horrify parents, but at the same time, leave their kids grinning maniacally.

The craft and sheer detail that went into Splatterhouse’s horror set-pieces made it something of a pioneer – even if it wasn’t exactly the first game of its hype. In the home computer and console markets, smaller developers had been turning out horror games for years; the Atari 2600 received fairly low-rent licensed games based on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Halloween franchises, while the ZX Spectrum’s obscure action adventure Go To Hell was full of tiny demons and disembodied heads.

In arcades, there were far fewer precedents for Splatterhouse’s boundary-pushing brand of gore. Death Race caused a ripple of controversy in 1976, but that was because of its theme more than its visuals – running over tiny stick men in a car was considered beyond the pale back then, making it a Carmageddon for the Gerald Ford era. No, Splatterhouse’s closest forebear was arguably Chiller, a horror-themed light gun game created by the same team that made Death Race. Taking place against a backdrop of torture chambers and haunted houses, Chiller was gory, crude and faintly unseemly.

But where Chiller was a relatively obscure title made with an evidently small budget, Splatterhouse was in a different league in design terms. Sure, the action’s sluggish and simplistic by modern standards, with its 2D action making it the crazed cousin of Sega’s Altered Beast, but it looks and sounds superb. When Rick fires a shotgun, there’s a blast of smoke and crimson sparks – an impressive detail to spot in an arcade game circa 1988.

What’s not clear is whether Namco had hoped that Splatterhouse would gain wider infamy through sheer shock factor alone; if it did, then the plan backfired somewhat. Far from making headlines with its violence, Splatterhouse simply drifted under the radars of culture’s self-appointed watch dogs. Splatterhouse wasn’t widely purchased by arcade owners in the west (probably because they were nervous about all that bloodshed), but cabinets certainly turned up from time to time in the UK – this writer has clear memories of spotting one in a British seaside arcade at the end of the decade.

All the same, Splatterhouse was something of a cult hit, particularly when it appeared on home consoles. The PC Engine (or TurboGrafx-16) received a port in 1990, and while it had some of its more extreme instances of splatter snipped out, it still provided a faithful approximation of the arcade’s frenzied massacre. There were sequels and spin-offs on consoles, too: Japan got Splatterhouse Wanpaku Graffiti in 1989, which was a kind of super-deformed parody of the arcade game shrunk down for the Nintendo Entertainment System (or Famicom). The Sega Mega Drive (or Genesis) received two sequels, which continued the bloody saga well into the 1990s.

Even these home versions didn’t generate much controversy, though, despite Namco drawing attention to the game’s content itself. On the cover of the TurboGrafx-16 edition, a splash of blood highlights the warning, “The horrifying theme of this game may be inappropriate for young children… and cowards.”

Try as it might, Splatterhouse simply didn’t horrify adults in quite the same way as another title first released in 1988: the side-scrolling arcade shooter, Narc. That game contained digitised 32-bit graphics, a drug war theme, and action that saw criminals blown apart with rocket launchers. Instead of Splatterhouse, it would be Narc’s war on crack cocaine that captured headlines.

Four years later, the soft-focus sleaze of Sega’s Night Trap and the gory fatalities of Mortal Kombat finally caught the attention of politicians in the US, leading to the introduction of Entertainment Software Ratings Board in 1994. By the time Namco’s disappointing Splatterhouse reboot emerged for consoles in 2010, its cover carried a genuine “Mature” rating – not the joking public health warning the original bandied about two decades earlier.

Still, while Splatterhouse didn’t gain the instant infamy of Mortal Kombat or Narc, it nevertheless garnered a much-deserved cult status. The game was a real trailblazer, too: with Splatterhouse, Namco was testing the boundaries of what was acceptable in arcades of the late 80s, paving the way for the similarly schlocky games that followed.

As we’ve seen, the series continued on consoles, but in the arcade, Splatterhouse remained unique among Namco’s otherwise bubbly canon. Before he worked on Splatterhouse, designer Akira Usukura crafted the graphics for the hit spin-off, Pac-Mania. The year after Splatterhouse, Usukura designed Rompers, an obscure maze game featuring a gardener in a straw hat.

It was as though Splatterhouse rose up from Namco’s collective imagination like a demon, briefly found its physical form in a singular arcade brawler, then vanished again into the depths of hell.