Modern technology isn’t all it’s made out to be: in Demons Of The Punjab, we saw the sonic screwdriver break for the second time in a row. The previous week, the Ptinga made a tasty meal out of the trusty device, though of course, it couldn’t stay away for long. As the Doctor brightly informed us, the sonic screwdriver now has a reboot setting. It was a weak moment in an otherwise tightly plotted episode, but then, consistency is not necessarily a requirement in Doctor Who. The polarity of the neutron flow can be reversed as many times as the writers please… so long as it’s in service to the plot. But Doctor Who has been oppressed by the sonic screwdriver now for quite some time. Once merely convenient, the shrieking metal stick has become indispensable.

The Woman Who Fell To Earth teased us with the bold decision to present the Doctor without her gear – no TARDIS, no screwdriver. The choice spoke to the vast potential series eleven has to chart its own path, brushing away the cobwebs of accumulated history. But this opened space didn’t last. By the episode’s midway point, the Doctor had already built herself a new sonic, and the TARDIS appeared on cue in the second episode.

It might seem inconceivable to imagine the Doctor without these familiar apparatus, but it’s not unprecedented. The Pertwee era began with a similarly bold move – grounding the Doctor on planet earth, with his ability to pilot the TARDIS removed and his access to non-Earth technology minuscule. Here, though, the third Doctor’s writing team stuck with their premise. We watch the Doctor navigate mundane earth life, worse, military life, and learn who he is without his toys. The upshot: still a hero, albeit a crankier one.

During the Tom Baker era, the series found itself laden with another deus-ex-machina device. K9, everyone’s favorite robo-dog. K9 was a lovable bantering partner, with access to a vast data-bank and, more pertinent, a laser ray gun, but at some point audience and writers grew sick of every tense encounter ending with K9’s intervention. The writers bit the bullet and wrote the dog out.

There are, of course, solid and functional writing reasons for the sonic screwdriver’s ubiquity. In Classic Who, the Doctor was free to spend precious minutes occupied by mundane problems like getting out of locked cells and obtaining information from reluctant officials. But NuWho‘s Doctor simply doesn’t have the time. A quick buzz of the sonic screwdriver and the door clicks open, the computer reveals its secrets, and the dreaded filler has been successfully circumnavigated. At this point in NuWho‘s run, though, it’s worth asking whether this convenience has come with a cost. Has the Doctor become nothing more than a techno-wizard, solving problems with a flick of her wand? Isn’t what we love and look to most in Doctor Who the Doctor’s willingness to engage and question?

In The Tsuangra Conundrum, the Doctor paces down the undifferentiated white corridors, in search of information. She ignores the medic Astos’ attempts to engage her in conversation, instead aiming her screwdriver over his head, and reading the computers herself. It’s a simple moment, easy to lose in the pace of the narrative, but for me it was a telling one. We’ve lost something, if the Doctor is no longer the person asking questions, rather than reading answers from the narrow edge of her screwdriver, when the Doctor no longer needs to engage with the minor characters populating each episode’s quickly constructed world. On the level of plot construction, the sonic screwdriver allows the writers to bypass engagement between the Doctor and the other characters until their requisite ‘character moments’. The effect becomes one of clunky, telegraphed characterisation, lacking organic verve.

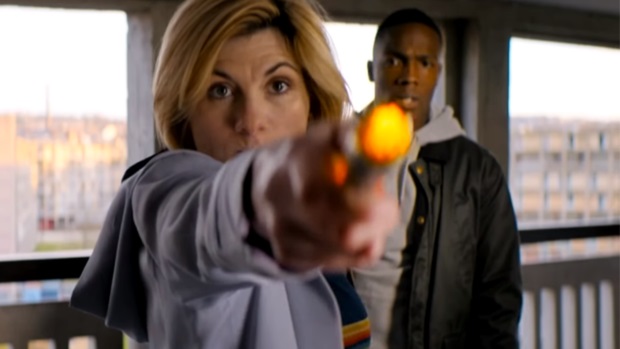

This problem – and its potential solution – was very much on display in last weekend’s episode, Demons Of The Punjab. In the first half of the episode, it’s hard to hear anything over the sonic screwdriver’s constant shrilling. When the Doctor and co are dropped into the alien’s mysterious lair, the Doctor once again chooses to read the answers off a screen, rather than asking questions of the aliens themselves. Instead of discourse, there’s metallic buzzing.

It’s not until the sonic screwdriver breaks that the real plot can get underway. Without the sonic screwdriver to manufacture technical deus-ex-machinas, the Doctor is forced into actual conversation with the Thijarians, and from this learns their true nature – not deadly assassins, but benevolent witnesses. The moment of revelation is powerful, but it’s hard to ignore that it only was made possible by the show’s habitual dependence on the sonic screwdriver to give quick answers and last-minute escapes.

The fundamental problem faced by NuWho is still its punishing time limit, the set fifty minutes in which the Doctor must enter a new situation, uncover a problem, be in grave danger, escape grave danger, and save the day, hopefully with character development thrown in. Moffat chose to address this problem through increasingly convoluted season arcs, with re-occurring characters and two-parters. Chibnall, who has vowed to do away with all old villains and abstain from two-parters, has left the show in a self-created bind – series eleven has committed to prioritising characterisation, but meaningful characterisation can’t be streamlined.

Demons Of The Punjab more than any other episode so far in the season has succeeded at drawing organic, nuanced character portraits of minor characters. Prem doesn’t merely shine at his moment of sacrifice – his humanity, compassion, and personal tragedy are on display throughout the whole episode, building brilliantly to the powerful finish. His brother, Manish, managed to bring some complexity and empathy that’s been lacking in the season’s other antagonists. The characterisation succeeds because it is given space to breathe.

There’s a lesson in Demons Of The Punjab, if the show is willing to heed it. Silence the sonic screwdriver. And let the characters speak.