Director Doug Liman’s never been one to back away from a fresh challenge. Whether it was making the leap from low-budget indie movies like Swingers and Go to expensive spy thriller, The Bourne Identity, or the knotty problems of making a time-paradox movie like Edge Of Tomorrow, Liman reliably goes for left-field project choices.

In The Wall, Doug Liman does something rare among established directors: he goes right back to basics. Shot for just $3m, The Wall is a lean, taut thriller set during the second Iraq war. Aaron Taylor-Johnson and John Cena play a pair of soldiers who, while scoping out an oil pipeline in the middle of the desert, find themselves pinned down by a sniper with a deadly aim. It’s intense, pared-back, and a marked change of pace from the bigger productions Liman’s made over the past few years.

With his latest film out now in the UK, and American Made, his drama starring Tom Cruise on the way very soon, we spoke to Doug Liman about the challenges of making The Wall, the studio response to The Bourne Identity and its cultural impact on release – and what we can expect from his sequel to Edge Of Tomorrow…

An obvious question, I suppose, but what made you choose such a small, contained project in the midst of the other things you’ve been making?

I loved the script, and different scripts require different sized productions. So I never really left the mindset of making small movies even when I’m doing a bigger budget movie. I’m interested in the kind of character work that is more in independent movies. I’m interested in the kind of anti-establishment ethos that goes with making an independent movie. I like to bring that to studio films – usually to the consternation of the studios.

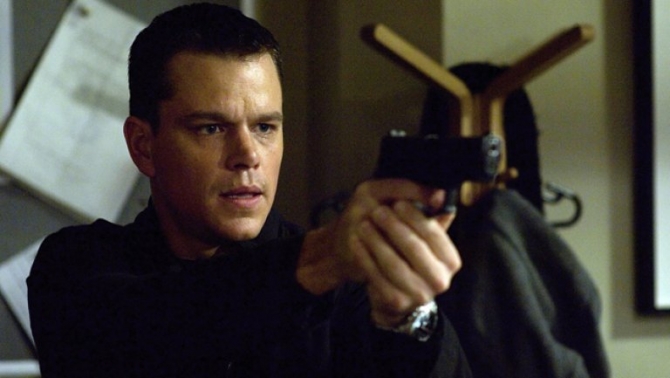

When I was making Bourne Identity, I wasn’t making a dumb action movie like they were expecting it to be. And even the style of shooting, Bourne was my first non-independent movie, my first studio film, but I was running around Paris with Matt Damon shooting in places we didn’t have permits to be in. That honestly gave the film its shaky, handheld feeling, because we were running into places like the Gare du Nord without permits. I had the camera on my shoulder.

The opening of Edge Of Tomorrow may be the most independent thing I’ve ever done. I filmed Tom Cruise in my editing room, and he did his own hair and makeup. So I’ve never been far from making an independent movie. But The Wall, what makes the story so riveting is the scale – that you’re at ground level with these two soldiers. There’s no help coming, there’s no cavalry, and there’s no cutting away to somewhere else. The soldiers are trapped there and you’re trapped with them.

I’ve always been interested in giving the audience a first-person experience in my movies. If Jon Favreau’s going to Vegas for the first time in Swingers, I want the audience to have the experience of going to Vegas for the first time. In fact, I filmed my own first arrival into Vegas, because I had never been to Vegas before – the first shots of Vegas in Swingers are my first views of Vegas.

In The Bourne Identity, I wanted to give the audience the feeling of being in the car with Jason Bourne, not just watching him drive but be in the car with him, and The Wall is the continuation of that immersive filmmaking style. Where you’re trapped behind the wall with Aaron Taylor-Johnson – for better or worse you’re trapped there with him.

I thought it almost feels like a first-person videogame, a bit like Edge Of Tomorrow. But then when the pain hits, you realise just how real the story’s going to be.

I make unconventional superhero films. Jason Bourne is a version of a superhero. Tom Cruise has the super power in Edge Of Tomorrow. These modern American soldiers are a version of a superhero, with the firepower they have, all of the gear they carry into the field, they’re like Iron Man. And the weapons are so ridiculously powerful. But it’s real; the thing that most captivated me about The Wall was how extraordinary the adventure was, yet it’s totally real and grounded. You don’t have to exaggerate any of it.

I get the impression the way you choose projects is, you pick things you’ve never done before, and you’re not sure how you’re going to do them.

Yes. Very much so. And also, worlds I’m interested in. Like, I didn’t grow up with friends in the military, but when I read The Wall and started talking to the few people I did know in the military, to get inside that world, I became fascinated with it, in the way that my father’s work in Washington exposed me to the American intelligence agency, which led me to make The Bourne Identity. I’m very much interested in learning about different worlds, immersing myself in them and then sharing that with an audience. But from a filmmaking point of view, I’m looking for challenges, and I have a very short attention span.

The idea of making a film with two actors, and for a lot of it one, terrified me. Because I don’t like movies like that – I like movies where you change location. When movies are great, I’ll watch two actors on screen, but it’s a terrifying challenge for someone with such a short attention span as I have. To do something that by definition needs to be claustrophobic. There’s no help coming for these soldiers. It’s a kind of film that gets more intense and riveting the longer you go, trapped behind the wall with them.

There’s the interesting reversal where the Iraqi soldier has the upper hand, and the well-armed American military guy, his weapons are effectively useless because of where he is.

Yeah. It’s tackling something in the Iraq war without talking about the war itself. I made a film called Fair Game set in Washington, and it was very much about the war, should we go to war. You can have those conversations when you’re in Washington DC, or in a coffee shop in London or New York City. When you’re in the trenches, you don’t have that luxury. And if you’re in the trenches, the other guy’s the villain. Because he’s trying to kill you. There’s no other way to look at it.

How has your approach to filmmaking evolved since Bourne? I know you’ve said that every film’s a film school, so has it changed over the past 15 years?

Um… [a long pause] Uh. Probably… I don’t know if it’s changed, because I’m still drawn to characters on adventures. Like, that’s an itch I’m still trying to scratch. Favreau going on an adventure to Vegas in Swingers; Jason Bourne’s adventure across Europe. The adventures of these two soldiers in Iraq in The Wall. I’m still captivated by people leaving their ordinary lives and going off to have big adventures. And, do adventures still exist? Have we so tamed our world that the adventure’s gone? I keep finding ways where it’s alive and well here and alive and well there. You can still find adventure.

Even Edge Of Tomorrow has a sense of realism, like on the beach with your big fight in the sand. It feels like an element of realism’s always something you’re looking for in your movies.

Yeah, because I’m interested in characters. No matter how extraordinary the situation, I’m really interested in how people act when put into extreme situations. What was incredible about The Wall is that it was the most extreme situation that I’ve put any character in any of my movies, and it’s also the most honest. It’s the least made-up; it’s the one that’s been repeated hundreds of times over the past 10 years in the Middle East. I hate to talk about soldiers fighting in connection with entertainment value, but it’s important for me for the stakes of The Wall to be gut-wrenching and real. It’s a movie that capitalises on the entertainment value of war, but by no means glamourises it.

No, and it makes guns frightening in a way that films often fail to do.

Yeah.

Do you think you’ve improved at playing the Hollywood game? Working with studios and producers?

Um, a little better. I’m a little less combative, but the day I’m not seen as combative at all would worry me. Because it is a business and it is a system, and it doesn’t always encourage originality. I’m in a unique position, because so many of my films have been original and they’ve been successful, but I’m brought projects where people are looking for something conventional from me. When I started working on Edge Of Tomorrow, we were working on the script and a draft came in that was awful. My studio executives loved it, and I was going to tell them how awful it was, and what idiots they were, and my agent at the time said, “You don’t always have to be the bad guy. Why don’t you let someone else point that out. It doesn’t always have to be you.”

So that was probably the one thing I’ve learned. To have a little bit of patience, because movies are my life. They’re my babies. I don’t have children, and I’m like a mother lifting up a car if their kid’s trapped under it – there’s nothing that gonna stop me from trying to protect my movies. Whatever happens to me is irrelevant. Because I come from independent movies, I loved making The Wall, I’m happy to make independent movies, the studios don’t hold any power over me. Because there are only a few studios out there, but I’m happy making independent movies, so there’s no threat they can lord over me.

The thing I’m terrified of is making a bad movie. I was shooting a commercial in the most dangerous wave in the world, Teahupoo, and we were in this wave for five days. I get equally terrified when I’m making a commercial that it won’t be good. If I’m making something, my heart and soul goes in it. And I found on that commercial, because I was legitimately worried about drowning every day – we were out on the waves on jet-skis – that the fear of drowning was way more comforting to me than the fear of making something bad. That was the set I was most happy on, because I could deal with the fear of drowning.

So the fear of creative failure is worse…

…worse than anything.

It’s interesting, because it feels to me that Hollywood studios are in a bit of a double bind; they recognise that unpredictability makes for interesting films, but at the same time, it makes them nervous.

Yeah, it’s a crazy business we’re in, because millions and millions of dollars are being spent on art. When I finished Bourne Identity, the studio hated it before it came out. They said it doesn’t look like other movies; there’s no one who knows anything. They wrote it off. They were like, this is a huge disaster. They stopped advertising it. The main writer on the movie arbitrated against himself to not get sole credit; everybody was running away from the movie before it came out. Not me. They were running away from me. It just goes to show, given the success of the movie – the fans loved it. Even when the movie’s done, the studio doesn’t necessarily know whether it’s succeeded or not. You have people investing hundreds of millions of dollars in a product whose success can only really evaluated by the fans.

How did it feel after all that, when you started to see other films take on the stylistic ideas in Bourne? Let’s face it, you changed the Bond franchise in a way.

You know, that was the most surreal thing. I always wanted to make a James Bond movie my whole life. I didn’t grow up like Quentin Tarantino, watching esoteric art films at the video store. I’d go to the multiplex and see big, mainstream movies, and I’d go, “I want to make one of those one day.” I always wanted to make a James Bond film, and they only seemed to hire British directors, and I’d made Swingers – they were never going to hire me for a James Bond film off Swingers.

I felt so insecure while I was making The Bourne Identity that I was making a poor man’s spy movie. There was someone on the set who had the Mission: Impossible ring tone on his phone, and every time his phone rang it drove me nuts because I was afraid my movie was never going to be as good as Mission: Impossible. It was never going to be as good as James Bond.

So it was really surreal afterwards to go and see the next James Bond film, and be like, “Oh, I did make a James Bond film, because now the James Bond film looks like The Bourne Identity.” So given the emotional insecurity I bring to my craft, that was really surreal. I would still love to direct a James Bond film, but I’m not sure if I have or haven’t.

What do you think more generally about the state of big Hollywood movies? You said that you grew up watching mainstream films, what films have impressed you lately?

I think there’ll be a half-dozen decent films that’ll come out this summer, and that’s pretty good. I think the American studio system, despite the fact they’re so fixated on franchises, there are a number of original movies coming out that should give all of us faith and confidence that there’s still a place for filmmakers to make big, original movies.

Yeah, because on one hand we have directors who have the clout to make things like Detroit or Dunkirk, on the other there’s a section of Hollywood where the directors are heavily overseen by the producers. They’re kind of almost expendable in a way.

Yeah, when you get to the franchises – look what they just did to the directors of Star Wars [the untitled Han Solo spin-off]. When you get to the franchises, it’s more like TV; the producers are king, not the directors. But luckily, whether it’s the success of Wonder Woman or Spider-Man, there are still original voices shining.

One thing I was going to ask with regard to The Wall is, I wonder why more filmmakers, between making big films, don’t do what you’ve done – get a couple of million dollars, a camera and a couple of actors, and make a small movie.

Because it’s terrifying. Because you have no safety net, no security blanket. The bigger movies, there’s so much money, and so many people invested in the film being a success. When you make a film like The Wall, there’s only a downside here for me. The danger of that is something I find appealing, but I may be a glutton for punishment!

Do you think there’s a fear of looking ordinary for some established directors, as well? If you’re respected for making big movies, then you make a small movie and it looks like…

…a small movie!

…yeah, a small movie, then that will lessen your credibility?

For sure. Or it could expose you, because you’re not that good. It’s easy to hide behind big movie stars and big spectacle. The filmmaker’s a little bit more hidden. Then you make The Wall, you couldn’t be more exposed. I think that… I’ve often thought there are these charity fundraisers where playwrights have to write a play overnight. I thought, you know, someone should do that with a short film script. They should pick one mainstream director, give say Steven Spielberg the same short script, and the same budget as four students, and see who makes the best short film.

That terrifies me, right, because you might get exposed. Your film should be better. And what if it’s not? I’ve never seen anyone do that, but I’ve always thought… so in a way, The Wall is my version of doing that. Stripping away all the resources that have built up around me. The ability to attract big stars and big budgets, big spectacle. And to be… it’s my own personal western. I’m gonna leave behind all those things and it’s just gonna be me.

And it works. It’s a raw, intense film. I was wondering about Edge Of Tomorrow, and its title changes. I was wondering what the story was behind the scenes there.

So the book was called All You Need Is Kill. Japanese. I was making a comedy – an action comedy, and All You Need Is Kill didn’t feel like it was the tone of the movie I had made. The studio wanted to call it Edge Of Tomorrow, and I wanted to call it Live Die Repeat. I fought vehemently and lost. And then when the film came out and people loved it but the box-office wasn’t as good as it should have been, I really railed into the executive at Warner Bros who’d insisted that Edge Of Tomorrow was the better title.

I was like, “It clearly is not. You were wrong.” I committed the cardinal sin of telling somebody in Hollywood when they’re wrong, like, literally – I ended up having to call the person and apologise for pointing out that they were wrong. And they started titling it the title I always thought it should have, which is Live Die Repeat. But they tiptoed around it, and when we make the sequel, it’ll be permanently titled Live Die Repeat. The sequel will be Live Die Repeat Repeat.

I can’t wait to see you do with this one. Because I know you’ve said…

It’s really original. I mean, that’s partly why the title had to be something a little bit more unconventional. And that’s why we’re even talking about a sequel, because we finished Live Die Repeat, and nobody wanted to go back to that world. The suits were so heavy and uncomfortable and the story issues with the time travel were so vexing. Like, you don’t have to talk to a scientist to find out that humans will never travel through time. Just talk to a filmmakers who’s tried to put time travel in a movie. The story paradoxes that crop up are so taxing that at one point the studio suggested we get rid of the whole dying repeating the day [concept].

Oh God.

So, we felt like we got out of that by the skin of our teeth. Like we came through a firestorm and got out the other side and were like, “Okay, nobody’s interested in going back into the burning building”. But the fan support and affection for the movie has been so extraordinary that we couldn’t help but react to that, and start talking about a sequel. This is not a conversation that started at a studio level.

It started with Tom and I working on American Made, and people came up to Tom and myself to talk about Edge Of Tomorrow – with such affection that we couldn’t… with what was being written about it online, we couldn’t help but start talking about a sequel because the fans were talking about it first. Then we came up with an idea that we loved so much and that is so original – it’s why the sequel’s gotta have an even crazier title, because the idea’s so outrageous, and so smart and clever. It feels more original even than the first movie. Tom and I and Emily are talking about going back into the trenches.

This time they want the suits to be made a little lighter. The film was emotionally taxing, because the story was so challenging to work out, but it was physically taxing because those suits are so heavy.

Do you think it’ll be made at a similar budget level?

It’s my hope that it’s smaller. I always have thought that the smart way to make a sequel is at a slightly lower budget, not a bigger budget. Because what people love so much about Edge Of Tomorrow are the characters, and we have a story that’s character-driven. That’s the reason to make a sequel, because of the characters and the world. But it’ll be a studio film – it won’t be on the scale of The Wall.

It’s just really smart. Chris McQuarrie as a close confidant – he’s worked on all of Tom’s films. I got into a room to talk about the sequel and we got into a creative screaming match that suddenly felt like we were back on the set of Edge Of Tomorrow. For a moment it felt like we were repeating the experience of the movie – like we’re repeating the day. And what was extraordinary was, we got from screaming to brilliant idea, what took six hours before took two hours this time. So we’re gonna repeat the process, but do it more efficiently.

It sounds really exciting. I can’t wait to see that.

I can’t wait to see it either. I pitch the story all the time at dinner tables, to my friends, and that’s when I know I want to make the movie, when I’m telling the story of it. At the end of the day, that’s who we are as filmmakers: we’re storytellers. It can be telling six people at dinner, or putting it on the screen to tell the story to a lot more people. It’s the same impulse.

Doug Liman, thank you very much.

The Wall is out in UK cinemas now.