One of the great pleasures of following genre cinema is the long, enduring onscreen conversation that’s taken place between movie directors from the East and the West, a creative push and pull which has resulted in some of the most boundary-pushing, inventive and important films ever made. When Akira Kurosawa wrote The Hidden Fortress, an airy homage to the John Ford Westerns he loved so much, he can’t have predicted its rollicking adventuring would be re-interpreted and sent into space by George Lucas to form the basis of the most successful film franchise in history in Star Wars: A New Hope. Similarly, when Ringo Lam took the tropes of 70’s Eurocrime and American gangster movies of the 30s and 40s, and upped the machismo and stylised violence quotient to insane levels with 1987’s City On Fire, he probably didn’t anticipate that film being ruthlessly pilloried to form the basis of Reservoir Dogs, the film that properly introduced Quentin Tarantino to the world and revolutionised independent cinema in the 90s.

Despite this tradition of ideas being respectfully rallied back and forth across the Pacific, there are very few directors who actually got to ply their trade successfully either side of it. Of this select group it’s arguably John Woo, who along with Lam was the founding father of Hong Kong’s celebrated ‘heroic bloodshed’ genre (which counts Woo’s hits A Better Tomorrow, The Killer, and Hard Boiled among its more notable entries), who had the most interesting career, and has undoubtedly earned his place in movie history cemented as one of the greatest action movie directors of all time.

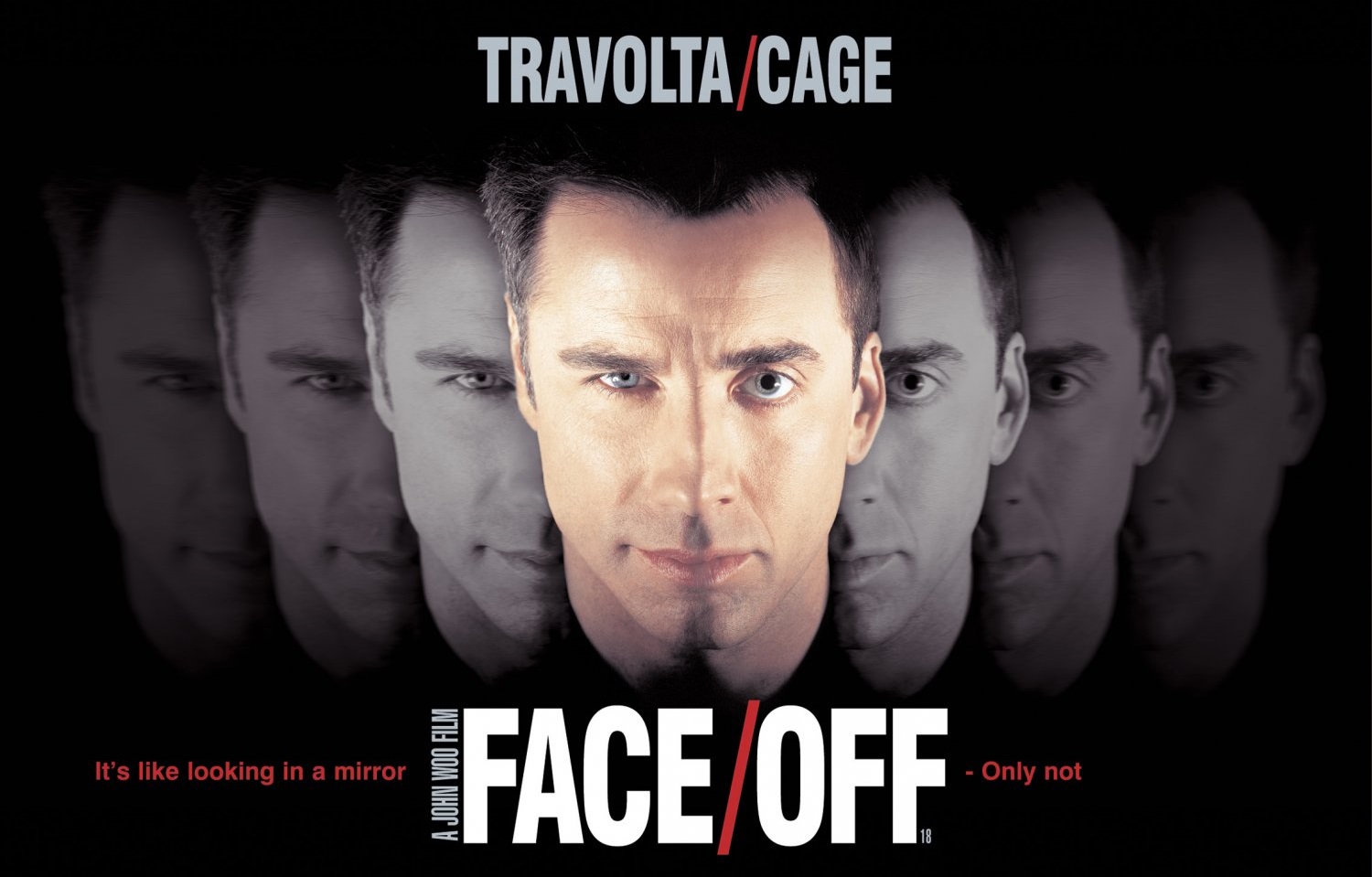

But while critics and movie historians will – rightly – concentrate on Woo’s staggering late 80s/early 90s Hong Kong work when writing the book on action movies, 1997’s Face/Off is by far and away his most interesting American work, and the point where the tension between the Eastern and Western influences in his films finally exploded into an utterly unique, incredibly satisfying mess.

Woo had worked on two Hollywood movies before Face/Off: 1993’s Jean Claude Van Damme vehicle Hard Target, and 1996’s Broken Arrow, a fun but formulaic chase thriller that is probably best remembered now for inadvertently giving birth, for better or worse, to Ain’t It Cool News. Neither film is without its low-rent charms, but they were both classed as serious disappointments after the likes of The Killer and Hard Boiled, whose achingly beautiful slo-mo sledgehammer symbolism and furiously choreographed pyrotechnic violence felt genuinely epochal for action cinema in the 90s.

After the commercial success of Broken Arrow, however, Woo was trusted to impart a little more of his trademark flair on proceedings with Face/Off. On top of this, he also received several gifts in the form of a higher budget, a deceptively smart script, and two of the least inhibited actors in Hollywood.

In a tale not so much high concept as I-can’t-feel-my-face concept, John Travolta’s tortured FBI agent Sean Archer has been engaged in a battle of wits with demented pervert terrorist Caster Troy (Nicholas Cage) for many years, after Troy inadvertently murders Archer’s young son in an assassination attempt gone wrong. The conflict looks to be over once Archer puts Troy in a coma after an explosive shootout, but then the revelation of a catastrophically huge bomb buried somewhere in Los Angeles leads Archer to make the somewhat questionable decision to undergo experimental surgery and have Troy’s face appended to his, so he can go seamlessly undercover as the criminal mastermind and root out the location of the bomb from Troy’s family and cohorts. Of course, it’s not long before Troy wakes up from his coma, steals Archer’s face for himself, and all hell breaks loose.

Most cat-and-mouse detective stories have fun with the well-worn cliché that cop and criminal aren’t so different after all. Like every single aspect of Face/Off’s production, however, there is little room for subtlety and suggestion, so what is usually subtext gets ripped out from under the floorboards and painted on the walls in block capitals.

Somehow, it works, because after the initial exposition scenes (which are dealt with so perfunctorily and quickly as to almost be apologetic) this lunatic conceit is explored in a series of ways that are at worst dramatically interesting ways and at best genuinely clever. One of the key things that separates Face/Off from its Jerry Bruckheimer/Michael Bay contemporaries is its interest in its characters: while the action set pieces are fantastic, the bulk of the film is spent exploring the consequences of the face swap either through Freaky Friday fish-out-of-water comedy (Troy as Archer teaching his daughter how to shiv a groping boyfriend) or Kafka-esque existential horror (Archer as Troy realising he’s trapped in prison as his nemesis sleeps with his wife).

It’s this sly and knowing air that permeates the script that makes the film feel more akin to something by the king of high-concept action sci-fi, Paul Verhoeven, albeit one that replaces the piercing satire with hysterical family psychodrama. And despite appearances, this is a sci-fi film, complete with an elongated set-piece in an elaborate, dystopian prison replete with convicts wearing magnetic boots, although its fantastical elements are deliberately played down – in fact, Woo’s major contribution to the script was to strip it of its futuristic setting, arguing that if the film-makers did their job properly, audiences would buy into the central concept without requiring the caveat that it be set in a far flung dystopia.

He was proven right, and setting it in the present day, of course, also allowed Woo to reach into his formidable box of tricks from the heroic bloodshed genre, and bring them to American audiences for the first time. It’s almost as if Woo knew that would be his one chance to truly work the style he had pioneered into an American film, and he doesn’t waste any time getting everyone up to speed.

You don’t need to watch more than ten minutes of Face/Off to realise that this is a John Woo joint – in that time you get the balletic, swan-diving, double-wielding pistol gunplay that was his trademark (at least until it was co-opted by The Matrix and the popular Max Payne game series); a slo-mo billowing cape as Cage’s lunatic villain emerges from a limo smoking a cigarette; faces exploded by bullets; shotgun blasts sending anonymous goons ten feet in the air; and a diegetic, thunderously operatic hymnal soundtrack being belted out by an actual church choir. He does show some restraint by holding back the fluttering doves, church shootouts, hospital gurneys used as weapons and Mexican stand-offs for later in the film, but that’s about it.

Crucially however, it doesn’t feel like a cynical John Woo greatest hits, as his bombastic use of religious symbolism and operatic violence is a perfect fit for all the melodrama. And of course, he’s matched beat-for-beat for maximalist excess by his two leads, Nicolas Cage and John Travolta.

Both actors were scalding hot properties at the time: Cage was fresh off the release of action mega hits The Rock and Con Air, and had a decent claim to being the most popular action movie star in the world. Travolta, meanwhile, was still riding high on the wave of his mid-nineties comeback via Pulp Fiction and Get Shorty, and was a credible A-list leading man in his own right.

To watch Face/Off is to be reminded that the nineties was the decade where the line between what was considered a good performance and frenzied overacting blurred considerably. The decade began with Antony Hopkins winning best actor for his pantomime Hannibal Lecter, and at some point during it Jim Carrey became the world’s highest paid film star, which should give you some idea of which way the wind was blowing. Now, in enlightened 2017, the trend in cinema leans much further toward understatement, so it’s a shock to see these two flail, scream and gurn through the film’s two hour plus running time as if they are in fact genuinely trying to act their way out of a series of increasingly sturdy paper bags.

Of the two performances, it’s funny to think that Travolta’s is by far the more understated, as it is still clearly a deranged exercise in rampant scenery chewing. That said, it’s still a decent performance: he has the harder job of the two, as he spends the bulk of a film as a bad guy trying to act like a good guy, which requires just a fraction more subtlety than his counterpart.

As for Cage: I’d hesitate to call his performance as Caster Troy good, but it is certainly impressive in terms of balls out insanity. There are moments here – Troy prancing around in a dog collar groping choir girls, Caster-as-Troy tearfully starting a prison riot, Caster-as-Troy tripping balls in front of a mirror – that are hilariously terrifying or terrifying hilarious, where you start to feel you’re witnessing a genuine psychotic break, and Woo just happened to be filming at the time. On the one hand, actors are so rarely permitted to go this big that it is genuinely thrilling; on the other, this is where you realise that this is the point where Cage began his transformation from charismatic quirky action hero to full blown meme, even though The Wicker Man was still a few years away yet.

Perhaps Cage being a punchline now is part of the reason why, 20 years on, Face/Off’s reputation seems to be diminished somewhat – it’s never mentioned in the same breath as the likes of Die Hard, Robocop, The Matrix, Batman Begins or Mad Max: Fury Road, as one of the more interesting, boundary pushing and enjoyable big budget Hollywood actioners. Cage’s reputation was to nose-dive soon after, following a string of cynically horrible films, and Travolta is only just about recovered from the debacle of 2000’s Battlefield Earth, the colossal Scientology flop which nearly ended his career for good. Equally, Woo’s Hollywood output returned to being disappointingly formulaic following the release of Face/Off, and he soon returned to Hong Kong to make a series of worthy but unremarkable wuxia films.

But Face/Off deserves to be revisited, and not only because, unlike a lot of its contemporaries, it eschews using the early period CGI that is all-but-unwatchable today, and has therefore aged considerably better. It should be revisited because it’s a piece of work that seamlessly blends its disparate reference points – high concept sci-fi, family psychodrama, Hong Kong heroic bloodshed, police thrillers, prison movies, Cronenbergian body horror – into something gloriously strange and unique, that somehow holds together as something that earns your emotional investment and attention, despite its up-to-11 chaos constantly threatening to vibrate the whole enterprise out of control. It’s so original and enjoyable that it’s only a matter of time before Hollywood remakes it some famous Chrises in the lead roles – in many way’s it’s surprising they haven’t already.

If Hollywood does choose to flog this particular horse, however, they shouldn’t bother with the remake, and just give us the sequel, with the ageing Travolta, Cage, and Woo all reprising their roles. Get that insane band back together, and show these mumbling noughties kids how to really make an action film. This trend for the understated can’t last forever. And when it does, we’ll know just who to call.