Casually dressed an pouring tea from a pot into a rattling cup and saucer, Luc Besson is relaxed and jovial when we meet him in a London hotel one sunny day in May. Chuckling and sharing anecdotes, he seems more like a guy recalling a busy yet fun holiday than a world-famous director who’s just made the most expensive movie in French history.

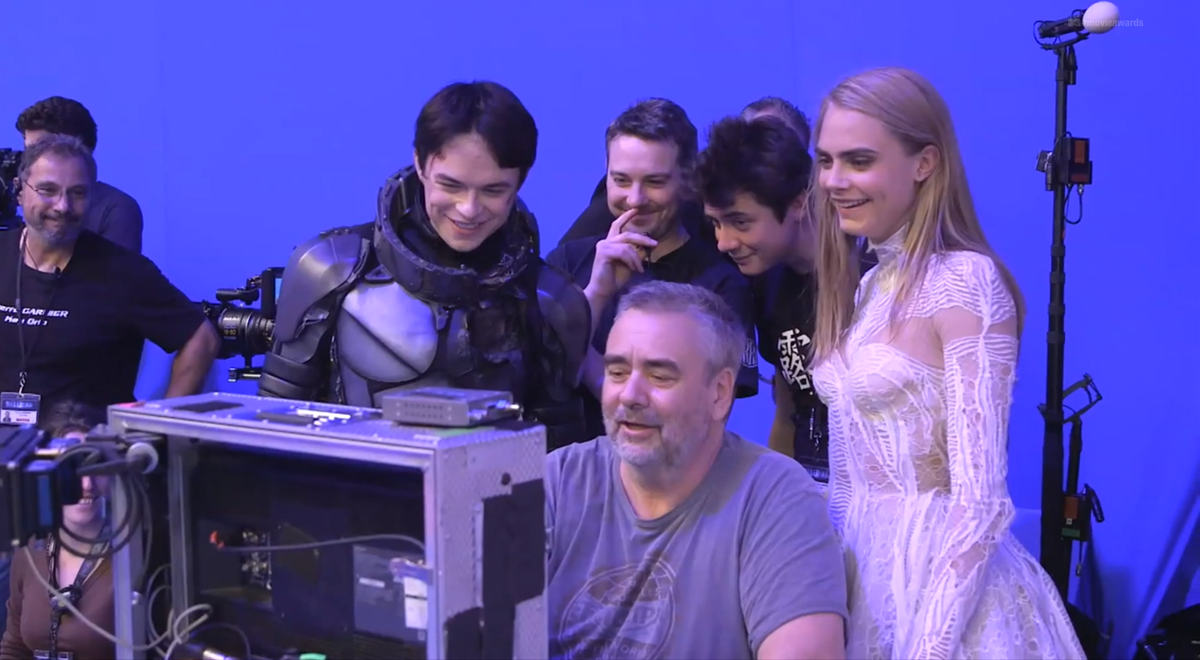

With a budget of $180 million, Valerian And The City Of A Thousand Planets is a big, bold and joyously eccentric space opera. Based on the French comic book series of the same name, it’s a return to similar genre territory as The Fifth Element 20 years ago. Starring Dane DeHaan as Valerian and Cara Delevingne as Laureline, special agents on a huge space station populated by aliens from around the galaxy, Valerian’s evidently a labour of love for Besson, who’s spent the best part of a decade getting the film made.

Ahead of its release in the UK, here’s Besson’s take on the making of Valerian, from writing to financing to its visual effects. Plus, we found the time to talk a little bit about female action heroes – something he helped revolutionise with his classic Nikita – and why, sadly, his comic book adaptation Adele Blanc-Sec won’t be getting a sequel anytime soon.

It’s the end of a long journey, making this film. Seven years, was it?

We bought the rights 10 years ago.

So what was your starting point?

Oh, the script. Without the script, you have nothing. First you choose the album – there’s 29 albums of Valerian, so I chose one. But you read an album in 30 minutes and a film is two hours, so you have to extend, you know? So I studied for a long time the script, the characters, what can help the story.

The big, big challenge of the story for me was the villain. Because I’m kind of fed up with the villains in sci-fi over the past couple of years. It’s always an alien coming; he’s a villain, he wants to destroy everything, and the hero wants to save the day. And it’s so difficult to get out of this pattern, because every sci-fi film since 10 years, specifically Marvel and DC Comics, it’s always, always the same. And I’m not 14 years old any more, so I need more when I go to see a movie. I said, “I don’t want to do a sci-fi like this. I want to do something different, more human.”

So my two acts were, the two heroes are basically Mr and Mrs Dupont – they’re two cops. He’s charming but a little bit stupid sometimes. He’s like… I don’t know how you say it in English…

Cocky is one word that springs to mind.

Yeah, he’s a little cocky. He always thinks he’s the best. But she saves the day most of the time. But if he has to fight with a sword – monsters of three hundred kilos, he goes. I really love that, that’s what I want. Real people, a real couple. When they say, “Did you read the memo”, he says “Yeah, sure.” We know he’s lying!

He doesn’t do his homework.

Yeah. It’s so typical of who we are today, in a way. I want to go there. I want the little story in the middle of a big story. Our villain, I tried to see in the history and the politics today, I came up with this mistake, people getting hurt, and we can’t pay them back because it costs too much. You almost have the feeling that it could’ve been on the news yesterday.

I thought that as I was sitting there. The conglomeration of aliens in space is like the European Union, isn’t it.

Yep, it’s the same. Nobody’s really guilty, because even the commander, when he explains why he did it – I don’t agree with him, but I understand his point. He has the feeling to fight for his people. He did it for his people, not for him. That’s why it’s so fresh, because it makes you think… we understand everyone [and their motivations] in fact.

You know a couple of years ago, someone said, “Oh the Iraqis have weapons of mass destruction, we have to go.” We all go: the English, the French, the Americans – we all go. Then there are no weapons of mass destruction. Oh! Really? So why did we go there? Then you realise, you see how society’s working, and it was a big inspiration for me. Because they say that evil’s in the middle of the station, we have to eradicate the evil – no matter what, we have to eradicate it. But they’re not evil.

How did you finance this, because it’s the most expensive film in French history, isn’t it?

Oh, it’s pretty easy [Chuckles]. Pretty easy in a way. I love this moment, in fact. You write a script for a long time, you get all your designers working for you, and then you have all your materials. Then you go to Cannes, you invite a hundred buyers for a hundred countries, put them all in a room, explain your film, they can read the script for two hours, and then they have an hour to make a bid. So in fact, at the end of the day, we got almost 80 percent of the financing. I love this moment, and I’m always very peaceful when I go there, because no matter what the answer is, I’m fine with it. If they say, oh my god the script is amazing, here’s the money, you say, okay, I guess my script is good. If they say, aahhh, we’re not sure, it just means your script is not good enough, and you have to work on it again. But at least you have an answer! You know, you have one or another, but at least you know.

It’s like running, and you get the time. Is the time enough to get to the Olympic games, or not? If your time is not good, go again in four years. Train, and you’ll probably go in four years. It’s not self-confidence, I’m just happy no matter what, because at least I will know.

On this one, I was lucky enough that it went extremely well, and we had 100 buyers and every country bought the film. Some people put some equity in it, so the financing of the film was not really the issue. Today, it’s little more than 90 percent of the film that is covered. So the financial was not the thing, what was complicated is, how can you keep the line of the content of the film, everything you want to put in it, on such a long term? I’m talking about the sentimentality, or the rhythm, the pace. To be sure your character is going like this [traces a smooth curve in the air] and not like this [hand veering like an out-of-control car].

That’s the most panicking thing. Almost probably like the guy who crossed the Atlantic on a boat before the technology; he has no compass. You just hope you’re right.

So it was pre-sold.

Yeah. If you’re not one of the big studios, like Warner Bros, that’s how you proceed.

I sort of assumed it might have been a different arrangement with that much money.

No, and the good news is that the film cost $180m, which is a lot, but I think a studio in Hollywood would make it for $250m. We saved about $70m, if you look at it this way! [Chuckles]

Also, I don’t think a Hollywood studio would necessarily make it.

No, there was a lot of un-trust from them at the beginning. But I have one fear, it is that most of the studios, already in their pipeline, a big sci-fi. Guardians Of The Galaxy, Star Wars, a couple of them. Fox has Avatar. I was just worried. I was worried that it was a way of controlling the enemy. By taking the film, they put it here [slaps back pocket]…

I see, so they’d buy it and effectively never make it?

No, they’d make it, but you’re always under their thing. I was scared of that. I would rather be a competitor facing them than being in a team and then… like, you’ve bought a huge football player, and then he’s on the bench for half of the season, you know?

I love the world-building in this, and the way you introduce the film: the cuts as you go through history. I wondered if that was your way of gently immersing the audience into the universe, because it’s so big and wild.

To have it grounded. Like, all this is true – it started in 1975! It grows and grows. I took it from the script. I took the scene out for a while, for a couple of months. It’s funny. And then I put it back, because I missed it.

So what was the process of shooting all these CGI sequences? I assume you have a similar virtual camera system to James Cameron for these?

No, I’m a little bit more old-fashioned than him. So I’m holding the camera all the time. I want to film actors no matter what. All the aliens, all the animals, anything that moves, it’s an actor. I don’t want Dane [DeHaan] and Cara [Delevingne] playing with a tennis ball. So if there’s an alien that’s three metres tall, I put down boxes, and I have an actor on the top of it playing. And I want him to play the alien – I don’t want him just to be there. The same for the animal who jumps on his arm? That’s a guy. I have a dog and I have a guy! It always makes it more human.

The three little pterodactyl creatures [see image below], for example – it’s three guys on their knees, for weeks. But I put them together for weeks, and they’re very friendly now, because the line has to be almost musical – du-dum, du-dum, du-dum. There was lots of rehearsal for that. Then Cara played with them, the three guys. So they were in grey, with dots, but it doesn’t matter – you forget after a while.

What was the most difficult scene to conceive and shoot?

We prepped so much. We were scared not to be ready. So actually at the end of the shooting, we finished three days earlier, because we were so prepped. But to keep track of this whole world in my head was complicated. The big market scene was [challenging]. I had a meeting with all the technicians, and I explained the big market. I explained it for an hour. And at the end of the hour, everybody’s smiling and nodding, but I can see that no one understands! It’s impossible. So I said, god, how am I going to do that? How am I gonna make them understand? Because when you watch it now, it’s easy. You put on a helmet, and you can see everything.

So what I did is, I took the 120 students from my school for three weeks. I put storyboards on the wall. We rented a sound stage, and I filmed the 600 shots one by one with them. So they were playing the actors, doing the grip, electrician, costumes, everything. They had a lot of fun, because I was holding the camera – just a D5, by hand.

I shot the 600 shots, I went to the editing room, I did the entire scene, and then what I did is, when we are in the desert, vision one, it’s slightly yellow. When we are in the tourists’ vision, which is through the glasses, so I see the other world, but I’m still myself, it was slightly blue. When you’re a merchant in the other world, and you’re looking at me, and I’m slightly blue, that’s what we call the merchant vision, and that’s slightly red.

So now when you watch the scene, it goes yellow, blue, red, red, yellow, blue, red.

Okay? So now all the technicians can understand. We have this video, which is 18 minutes long, on the set, and everyone can come and see what we’re doing. That was the only way we could make them understand!

I wonder, then, if that’s what the advantage of digital filmmaking is, that you can pre-visualise a scene like that relatively quickly and cheaply. But back when you did The Fifth Element, something like that wouldn’t have been possible.

The Fifth Element has 180 shots with special effects. This one has 2734. So it’s two world. But The Fifth Element, I’d shoot something and then the day after I’d watch the dailies. Now here, my editor was on the set, so when I shoot something, by the time I go to see him, it’s already in. Then I can say, “Hmm, it’s too slow. Let’s do one more take.” Much more efficient. And we have to do that, because the special effects need so much time. Some of the special effects work starts four months before shooting, so we start in September 2015.

How many teams of people did you have working on those effects?

Altogether, it’s 950 people. The two leaders were Weta and ILM. One has 600-something shots, the other has about 1000. And then the third company was Rodeo in Canada. Rodeo, I worked with them on the chase in Lucy, the chase with the car. So they’re very good when it comes to vehicles. They did all the space ships. Everything mechanical. Weta did the characters, the pearls, all the aliens. ILM did the entire did market.

As a filmmaker, that’s a completely different way of working. If you’re getting in these effects shots from three different companies in three different parts of the world, you must be sitting in France getting all these to review.

Reviewing at the beginning was once a week, then twice a week, then every day. I was in LA. Everyone is sending the shots to one office in LA. [My visual effects supervisor] is watching everything and then I come at 2pm, and I’m reviewing everything coming from everywhere. I give some notes, then at the end of the day, it goes back to everyone, and they work on it. Then the day after it comes back. In fact, it’s just two hours of work, shot by shot, and you just give details. That’s too slow, that’s too fast, maybe the hand should be higher. Maybe the colour’s not perfect.

The first shot you see, you can change it five times. That’s the deal. Five times I can give corrections, but after the fifth time, that’s it.

Wow, so you have to be careful about your decisions.

If you want to change it the sixth time, you have to pay!

I can see how that could get expensive.

Yeah, it’s expensive. But in another way, there’s a few shots that I let down, because I don’t need it in the editing. So I have a special box, so when we start the film, each shot, we have the length of the film, per frame, how many aliens in it, what is the movement, the storyboard, and the price of the shot. All of them. So if I cancel a shot at $10,000, I put the $10,000 in my box. Okay? For the entire film I have my box, and I save some money, and then when I need more money for a shot, [I take it out of the box]. So I was playing with the box for the entire film. And so far, so good! I’ve spent what I’ve saved.

What I appreciated as well, is that the film isn’t overwhelmed by action. A lot of the shots aren’t things exploding, they’re world building and detail. Do you think that it’s sometimes too easy for directors to get carried away with digital action sequences?

I think that most of the time, most of them are directors for hire, and the action scenes are done by the second unit. You see that sometimes in films and they talk, and it’s slow.

Shot reverse shot.

Yeah, and they talk for five minutes. And then dah-dah! Off it goes. And suddenly the camera is going everywhere – there’s no relationship between the way they film. Because not the same director, that’s all. Me, I’ve been on sets since I was 17. I learned my art from the ground. I’m like the guy who blew the glass – it takes 20 years to be great. For me it’s manual – I’m an artisan, you know? So I do every shot. I don’t have a second unit, I do all of them. All of them. Because I want a unity in the film.

So when there’s a chase with space ships, it’s pretty elegant, and you can see everything. It’s not like there’s editing that you hide little bits and you put in some sparkles so you don’t see. No, it’s there, you know? It’s very important for me. We work so much on the background of every alien. I have a bible of 500 pages. We know our shit. I’m not afraid to have the camera slowly do a 360. I have no problem with seeing things, like, we are there. Not cheating so much, as we see often.

Like when the alien gets out the pearls on the beach at the beginning, when she goes out of her house, we’re behind her back, we walk out with her, and we do a 360 around her with a 25mm lens. We don’t hide anything! When you watch it, you feel like you’re there.

A writer I once spoke to thought you might be quite influenced by Japanese manga.

Me? No. I’ve never read a manga in my life. My background is really in Mobius, Tintin, Asterix. It’s really the French-Belgian area. There were a couple of directors when I was young where I was amazed by the architecture of their shots. Especially Kubrick, for example, where everything is really…

Geometric.

Geometric, yeah, like an architect. If you have the opportunity one day, cut the sound, just watch the architecture, you can see the influence. Even though the subject of the films is so far away [from Kubrick], the fibre, yeah, a lot. I was influenced by Kurosawa a lot. Kurosawa I was very impressed by the way he did things.

Do you think you’ll do another Adele Blanc-Sec, veering off on a tangent?

It’s complicated, because I love the film, and I love her, she’s so sweet in the film. I would love to do others. The thing is, to get this quality, it costs quite a bit, and when you’re in the French language, you’re dead. You’re dead. You cannot afford, in French, to do this kind of film. You have to be in English, and I don’t want to do it in English. There’s something so French about it that I want to do it in French. So we’re kind of stuck, because the film worked pretty well, but not enough to do more, you know? So it’s too bad, but that’s life.

That’s such a shame. Your films generally have great female characters in them. Why do you think it’s so taken American action filmmakers so long to make something big like Wonder Woman? It feels like they should’ve done it years ago.

Well, it took forever for women to get the right to vote. It took forever for black people to be freed from slavery. It took a lot of time for the British to accept homosexuality, I heard [chuckles]. So when things are anchored in society, it’s not that people don’t want it to change, it just takes time. For many years in the 60s and 70s, the westerns, all these films, the gladiators, it’s about the guy. It’s about the muscles, and the girl is there to stay home and cry.

We have to wait until the end of the century, the 90s, the beginning of the 2000s, and Nikita was one of the first to push the mentality a little bit. Just to say, “Hey, women are strong. They can do things.” But what was interesting is, as soon as it appeared, it was very well respected. They were like, “Yeah,” nobody fought it. “I like it”, you know? That’s a good sign. It means there’s not a hostility deep inside people. It was just a tradition, and if you push it, sometimes, it works!

Luc Besson, thank you very much.

Valerian is out now in UK cinemas.