I think it is safe to say that I’ve never worked harder at anything in my life than Robot Wars. The show began in 1998 when lightly armoured wheelchairs would push each other about a bit and a 10-year-old me declared to my mother that I wanted to be on the show. “I’m not sure you’re old enough,” came her politely discouraging reply. Fast forward the best part of 20 years and I had taught myself the basics of robot construction, fought my way up through the ranks in the antweight class (tiny 150g machines rarely featured on the show but with a thriving community outside of it) and dabbled in a couple of naff attempts to build one of the big boys in the heavyweight division. I had lucked into the filming of the first series of the rebooted show thanks to my wonderful friends in Team Nuts and had since sunk all of my time, effort and savings into building my own robot, Jellyfish. I applied for the show and received a call saying I was in. Huzzah! I was going to achieve what I’d set out to do 20 years ago! This was the stuff dreams were made of!

It was here that the realities of filming a show like Robot Wars started to hit; the stuff that, no matter how hard they try, will never really come across on the TV. It is a show that asks more from its contestants and its team of technical experts than anything I can think of. The building of Jellyfish was relatively straightforward with only 2 occasions where it looked like my lack of skill would overtake me and the robot would never run. On these nights I had to be coached through by friends or I may have thrown in the towel. No matter, he was working, had been loaded into our hire van (more money) and we were on our way to Glasgow.

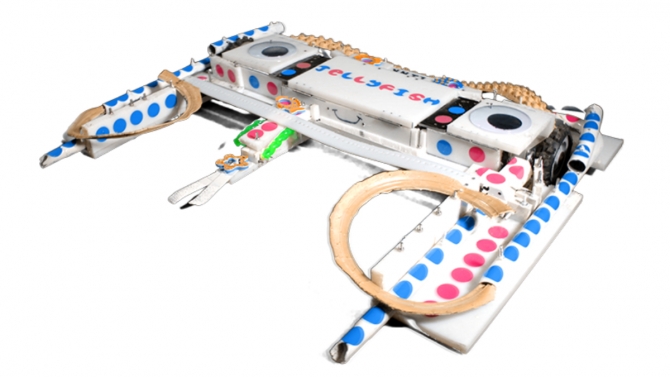

We were the very first team to arrive at the aircraft-hanger sized set on the Thursday morning. Having taken part with Team Nuts the series before I knew my way around already but there’s still something wonderful about seeing the Pits laid out in front of you, all empty tables, devoid of clutter and mess, with a single robot name card stuck to the corner. The calm before the storm, indeed! The child in me wanted to run around and check out who else had qualified but there was no time for that now. Jellyfish was unloaded from the van onto a trolley and wheeled straight in to a small room at the side of the Pits where ‘green screen magic happens’. First he was set on a large turntable and spun slowly. This is the shot that is then superimposed onto the battle screen on the show. He was then shifted to a small turntable to film a shot that is then added in to the team VT stuff that we’d filmed a couple of weeks’ previously. This was a comical experience as Jellyfish was one of the largest robots in the competition and hung over the smaller turntable like a child dressed as a sheet ghost for Halloween. A shout out here for the crew who manned this room. Not only were they stuck in here for the majority of the shoot, it was also the first time we’d had proper help lifting and carrying Jellyfish. At 85kg he was on the light side for heavyweights but trying to manoeuvre him around at home had been nearly impossible. Fans often asked afterwards “why didn’t you test the robot more?” Well, the only place there was room to take him out was our driveway and there were only two of us to do the lifting. The first thing that is pointed out about Robot Wars is the size and weight of the machines but the TV will never quantify what a pain in the neck they are. Any team will tell you that shifting them about is not part of the fun.

We decanted Jelly onto his pit table and went to fill out some forms. Forms are a key part of any TV production and my advice is to bring your own pen. Contracts, health and safety guidelines, rules… the show is a competition after all. There is no fixing or favouritism here. The reboot was built around fairness. What happens in the battles is what happened. They film each one live in one take and they are all kept in the show, even the rubbish ones. This makes the job of the selection committee so much harder. If they choose a robot that turns up unfinished or not working properly then often they just have to run with it. Every robot has to pass a safety check before they are allowed to compete and if you fail you may be replaced with a reserve team. Even for those that pass their checks, there is no guarantee that their robot will not die instantly in battle. This is the nature of the game. Remember when I said I’d sunk my savings into Jellyfish? It is not a show to be entered into lightly.

Back on set, a lovely man called James had conducted Jelly’s safety and rules exam and he had passed, which secured our slot on the show. Next came something that is a big part of any TV production – waiting! Two days of it, give or take. We had passed tech check by about midday on the Thursday and our fight was scheduled for Saturday morning, with two celebrity special editions of to be shot on the Friday. There was much to occupy us. Roboteers would turn up at various intervals with their creations so there was lots of marvelling over robots, scouting out the competition, meeting new friends and the like but, in a cold warehouse in Glasgow, even this can stop being fun after a while. On the Friday morning we had a team photoshoot with Jellyfish for the website and then had to mostly stand out of the way whilst the celebs did their thing. There is a small TV in the Pits with a live feed of the arena so that we can watch the fights. Sometimes these were hours apart and then the battle could last mere seconds. We schmoozed a bit with the celebs but their filming ran way behind schedule and we ended up heading back to the hotel before it had ended, finding out the next morning that it had gone on very late indeed. Again, I salute the crew. Long days, late nights, early mornings.

I didn’t sleep well that night and returned to the Pits the next morning feeling rather morose. Our fight draw featured 2 robots who I really feared and I was pretty much resigned to a round 1 exit, but had convinced myself that the effort and money would be worth it if Jellyfish just worked properly. We filmed our opening interview with presenter Angela and then resumed the wait. A couple of the robots in the opening melees had had trouble driving on the arena floor and, because Jelly was so low, they made us have a drive in the test box just to show that he was going to be able to manoeuvre. He ran beautifully, prompting a few teams to declare they hadn’t expected him to be as good as he seemed to be. We were ready to fight. We loaded Jelly onto a trolley and filmed our walk to the arena, then we stood backstage with Team Nuts whilst the previous battlers were swept out. We pushed Jellyfish into the arena with the crowd watching and filmed what is known as a ‘hero shot’ (the bit in the show where they say “From Antrim in Northern Ireland… Jellyfish!” and zoom in on you with the CO2 jets blasting) and then sat side by side with Nuts 2 whilst the complex process of arming up the robots took place.

One by one you are prompted to plug in your removable link (the on/off for the robot, an absolutely essential safety device) and drive across the arena to face the big pit release button. This is so that, if your robot does choose to have a fit of nerves, the danger is minimised. Again, Jelly drove fine. The arena was secured and we were ushered up into the spacious fight booths where we moved the robots into their start positions. A disembodied voice announced “Roboteers…stand by!” which is your cue to smile and wave at the crowd. Then came the famous countdown: “3…2…1…activate!”

The thing with robots is that everyone watching believes they respond a bit like a computer game, with perfect control to put them where you want, but every robot reacts differently. Even the best teams can be plagued with gremlins that they have no explanation for. Upon “activate!”, Jelly barely responded to my transmitter. Sometimes he drove without input, sometimes he caught my signal, sometimes he stopped completely. Add in the 3 other machines trying to write us off and it simply became a battle of survival. There were no tactics, no trying to pick someone else off, nothing but hope that two other robots would die before we did. It wasn’t to be. We lasted a decent while for the problems we were having, but we were out. I was pretty upset to go out for such poor reasons. Thankfully they cut our post fight interview because I was devastated and I don’t think I came across well. It wasn’t the losing, I was fine with that. It was the factors of loss. Jellyfish had got stage fright and that was it. We were booked onto a boat home for the next day, loaded the van and headed back to the hotel.

That night we got a call asking us not to go for the boat but to come back to the arena. One of our opponents was having technical issues and they had to withdraw. We were re-instated as the third place robot from the opening melee. This gave us two more fights to contend with. We swapped the radio gear in Jellyfish for the stuff that was in Nuts 2 which would solve the interference issues. I was so tired at this point and a recurring hip injury had resurfaced, so the pre-fight interviews at arena side had me speaking with a very hazy brain. Luckily, so much gets cut from the show and I’d like to thank the editors for not making me look like a hungover teenager, as I’m sure they had the material to!

Our next fight lasted precisely one whack. Opponent Terrorhurtz bashed one of our speed controllers with their big axe, which disabled Jelly instantly. The battle lasted about 5 seconds. Upon autopsy back in the Pits we discovered the speed controller was not repairable on site. We also discovered that one of our motors had taken some serious damage back in the initial melee. Teams offered us spares so that we could get Jelly fixed. This camaraderie is easily the best part of Robot Wars. Help comes from all sources.

Our final fight was against a robot who had been destroyed in its previous battle and was hobbling back into the arena a shadow of its former self. A few seconds after activate I realised Jelly also still had issues and the batteries were dying. A faulty charger was the culprit, but too late now. Safe to say this wasn’t the greatest fight ever. Both robots were simply trying not to die and it eventually went to the judges. We were awarded the win and, despite all of the problems, I finally felt elated. Even if it was against a half-dead opponent, a win at Robot Wars was not something I ever considered I would have to my name. I surfed this euphoric wave home and immediately ordered parts for the next version of Jellyfish. Another large chunk of money was spent.

We failed to win a spot on the next series. We applied, we waited and then finally received a phone call stating we hadn’t been picked but they would like to encourage us to keep trying in future. I was now experiencing the worst part of Robot Wars, the other side of the fence on which many other teams had sat. I had no money left and a robot I couldn’t do anything with. I had to sell up all the parts from the new Jellyfish to try and claw back some of my losses and stated I wouldn’t be trying again. With hindsight, I should have handled the rejection better. I had already been part of the show twice and many teams had not. I was upset at the waste of money, but the same is true for every rejected team and some of them may never get to experience the show first hand. I was doing the production team a disservice by being ungracious, the same team who had let me come play previously. They had their reasons not to take us and, looking back, that’s fine. The show still has a special place in my heart. Many of the people involved are genuinely brilliant and, despite the blows I had received, I doubt I could ever actually reject an opportunity to try again.

So these are my lessons. If you fancy a crack at Robot Wars, set yourself up for several possibilities before you even start to build. Firstly, it’s your money, your time, your effort. Entertain the likely possibility that it may all be in vain. Do not spend money you cannot afford to burn as I did. It can lead to some horrible situations. Secondly, keep in the back of your mind that you can test your machine ‘til doomsday but you never know what might happen in the arena. Jellyfish worked like a dream up until “activate!” and then it imploded. It is easy to see the fights on TV and think “I would’ve done this if I was driving!” but it really doesn’t work like that. Even the best roboteers are basically flying by the seat of their pants throughout. It’s a whirlwind and controlling your journey is rarely an option.

Finally, do not enter into it lightly. The teams work harder in their few days of filming than most do at their jobs. It is not a fun holiday. It is dirty, stressful and tiring. You snap at your teammates, you often feel low and miserable, and your appearance may be short and sour at the end of it. Spare a thought for the crew – for every hour you put into your robot, they put 3 times as many into making the show work. It is an experience that can bring out the worst and the best in people. It did in me. But what an experience it is. Despite all the heartbreak, would I do it all again? If I take heed of my own lessons and change my approach…well, I have a few ideas. Whether or not they have me back though, long live Robot Wars! There really is nothing else like it.