Few animation studios have been as consistent in their output as Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli. Founded in 1985, its animated fantasies are made with just the right blend of humour, melancholy and whimsy to make them appeal to audiences of all ages.

And while Studio Ghibli has embraced new technology in recent years – Pom Poko was the studio’s first film to use CG back in 1994 – it remains committed to producing animation using largely traditional, hand-drawn techniques.

Miyazaki is back out of retirement (again) and the whole studio is hard at work on his How Do You Live?, tentatively due for release in 2020, so we’re currently in a long lull between projects. So what better time to take stock of Ghibli’s output and pick their best animated features…

Laputa: Castle In The Sky (Tenkû no shiro Rapyuta) 1986

Borrowing the flying island concept from Jonathan Swift’s 18th century satire Gulliver’s Travels, Castle In The Sky was the first animated feature released under the Ghibli banner, and arguably their best. Set in an alternate Victorian era full of sky pirates and steam-powered war machines, this remains one of Miyazaki’s most action-filled, plot-heavy, yet purely entertaining films.

Relating the tale of two youngsters and their attempts to find the mythical flying castle of the title (actually a gigantic, Eden-like island where nature and technology exist side-by-side), Castle In The Sky contains some stunning character and mechanical designs, not least the ethereal, faintly tragic robots that guard Laputa itself.

Miyazaki was reportedly unaware that “Laputa” is Spanish for “whore”, hence Disney’s decision to release the film in the west under the redacted title of Castle In The Sky.

My Neighbor Totoro (Tonari no Totoro) 1988

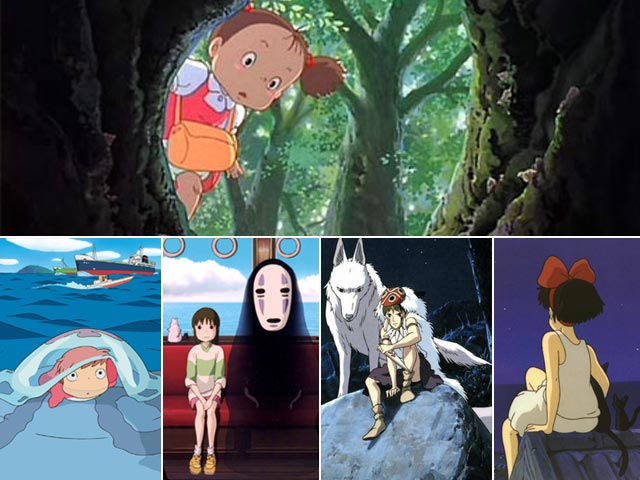

After the high adventure of Castle In The Sky, Miyazaki came back down to earth with the charming My Neighbor Totoro, a gentle and heart-warming tale of a little girl who discovers an entire forest of lively spirits.

Miyazaki has often said that he made Totoro to give city dwelling youngsters an idea of what the countryside is like, and the film certainly succeeds in imparting a feeling of wonderment that is now a Ghibli hallmark.

Its plot may be slight, but the strength of the characters, from the dust sprites, via Catbus, to the delightful, bear-like Totoro himself, invest the film with such charm that it’s impossible not to be drawn in.

Grave Of The Fireflies (Hotaru no haka) 1988

A starkly different production from Totoro, Grave Of The Fireflies was directed by Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata rather than Miyazaki himself. Nevertheless, the quality of Grave‘s animation and character design remains dizzyingly high, and the film is a heartbreaking depiction of two children’s struggle for survival in World War II Japan.

A mainstream picture that thoroughly dispels the myth that animations are for kids, Grave Of The Fireflies is, along with Mori Masaka’s earlier Bare Foot Gen, one of the most affecting and intelligently paced depictions of war in an animated feature, and will leave all but the most cold hearted viewers utterly shattered by the time it draws to a close.

Kiki’s Delivery Service (Majo no takkyûbin) 1989

Miyazaki returned to the fore for Kiki’s Delivery Service, an altogether lighter feature about the adventures of a teenage witch and her black cat. A less memorable film than the classic Totoro, perhaps, but still packed with typical Ghibli character and charm.

Miyazaki’s capacity for creating strong, likeable female lead protagonists is at the fore here.

Porco Rosso (Kurenai no buta) 1992

A film that indulges Miyazaki’s love for aircraft, Porco Rosso is set in 1930s Italy, and features a pilot cursed with the head of a pig. Along with planes and strong female leads, pigs are a common motif in Miyazaki’s films.

Miyazaki’s enthusiasm for his subject is present in every frame, with its aerial dogfights rendered with humour, energy and staggering attention to detail.

Pom Poko (Heisei tanuki gassen pompoko) 1994

An interesting departure for Ghibli, whose films are normally broad enough to appeal to all countries, Pom Poko contains numerous Japanese cultural and religious references that could baffle unsuspecting foreign audiences.

Again directed by Isao Takahata, Pom Poko is an ecological fable about a society of shape-shifting, mischievous raccoons and their efforts to protect their forest from the urbanisation project of 60s Japan.

Notable for its surprisingly common display of testicles (it’s not uncommon for raccoons to be depicted with prominent genitalia in Japanese tradition), Pom Poko is easily Studio Ghibli’s most anarchic feature to date.

The spectacular animation reaches its zenith in an enchanting ghost parade sequence, and the film’s often laugh-out-loud humour is undercut by a particularly stinging, unsentimental conclusion.

Princess Mononoke (Mononoke-hime) 1997

Miyazaki’s pet themes of nature and ecology are at the forefront of Princess Mononoke, a film which the director intended to make his last until its huge success convinced him to continue working at Studio Ghibli after all.

At over two hours long, Monoke is a punishingly long feature, and its singularly melancholy, downbeat tone may prove too much for younger audience members, but in terms of character design and animation this is vintage Miyazaki.

The colossal, ethereal gods of the forest are singularly captivating creations, and the film’s battle sequences are surprisingly visceral. Western distributor Disney wanted to cut the film to gain a PG rating in US cinemas, but Miyazaki quite rightly refused.

Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi) 2001

Miyazaki’s most obvious touchstone for Spirited Away is surely Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, but the Japanese master places enough of his own unique ideas onto the central premise to make the picture all his own.

Chihiro is a typically strong-willed female lead who finds herself lost in a fantastical alternate world of gods, spirits and dragons. Miyazaki created perhaps his strongest fantastical character design since Totoro in the shape of No-Face, an eerie, wraith-like presence who quickly proves to be a terrible glutton once confronted with a table of supper.

The first Ghibli film to earn an Academy Award, Spirited Away remains one of Studio Ghibli’s most acclaimed and lucrative releases to date.

The Cat Returns (Neko no Ongaeshi) 2002

Another Ghibli film with a female protagonist, 2002’s The Cat Returns was directed by Hiroyuki Morita, an animator on such classics as Lupin III and Akira.

A slight film in comparison to the epic Sprited Away, The Cat Returns is, like so many Ghibli films, memorable for the quality of its characterisation and design, particularly that of Muta, the lugubrious, overweight feline whose appetite soon gets him into trouble.

When high school student Haru saves a cat from being run over, she finds herself drawn into an entire secret kingdom of cats.

Ponyo (Gake no ue no Ponyo) 2008

Studio Ghibli’s Ponyo feels something of a return to basics after a run of increasingly intricate films. Taking the Hans Christian Andersen tale The Little Mermaid as its basis, Ponyo relates the story of SÅsuke, a gentle nine-year-old who encounters Ponyo, the titular fish-girl of the title, while playing on a beach near his home. Actually the daughter of the Goddess of Mercy, Ponyo’s decision to transform into a human proves to have destructive consequences for SÅsuke’s idyllic coastal town.

Less consistently entertaining than Ghibli’s earlier work (while charming, Ponyo’s human persona is less well-rounded than Miyazaki’s other female protagonists), there’s still much to enjoy here. SÅsuke’s mother is a believably flawed yet likeable character, and the depiction of the ocean floor, teeming with exotic and colourful life, is never less than dazzling.

The Wind Rises (Kaze Tachinu) 2013

Originally meant to be Miyazaki’s final film (before he changed his mind and started working on How Do You Live?), The Wind Rises feels like a swansong. Beautifully elegaic and deeply personal, the film tells the true story of Jiro Horikoshi, the man who designed the Zero fighter planes that played a major role in WWII. Essentially the story of Miyazaki himself, the parallels between both men are softy drawn – a tender self-portrait of an artist with his head in the clouds. The 1923 Tokyo earthquake gives the film its only real set-piece, with the rest of the story grounded in much more emotional details of Jiro’s life, love and dreams. Possibly Miyazaki’s least technically ambitious film, it might also be his best.