When the first episode of The Sopranos aired on HBO in January 1999, it seemed to come out of nowhere. Viewers and critics alike were spellbound by David Chase’s crime saga. On paper, the trials and tribulations of a New Jersey mob boss sounded like the stuff of trashy soap opera, but thanks to the pen of Chase and a host of phenomenal performances, it turned out to be one of the most rich and complex television dramas ever made.

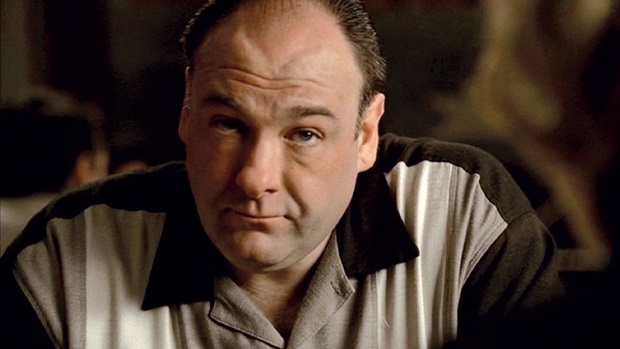

A lot of the show’s strength lay in how relatable the put-upon Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) was as a character. He might have been a high-ranking member of the Mafia, but he still had some very ordinary problems to contend with: a dissatisfied wife, mutinous kids, a suffocating mother, difficult employees and – perhaps most refreshingly of all – a tonne of mental health issues. Trying to make sense of his life, Tony battles anxiety and depression throughout the show’s six-season run.

Twenty years down the line, The Sopranos ranks amongst the most pioneering TV shows when it comes to portraying male mental health. Here’s how…

When it comes to mental health, tough guys aren’t so tough

“The truth is this therapy is a jerk-off. You know it and I know it.”

For all the bullets and bloodshed, it’s the quieter scenes in The Sopranos that were most compelling – and amongst the best are Tony’s therapy sessions with Dr Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco). This was because here, in the oak-panelled sanctum of Dr Melfi’s office, we were given intimate psychological access to Tony: his neuroses, resentments, fears, desires and deepest secrets. Not that he’s an enthusiastic client, having been referred to Dr Melfi after a spate of what he’s unwilling to admit are panic attacks.

If you’ve had therapy, you’ll know how progress and vulnerability go painfully hand-in-hand, amd how you have to place an astonishing level of trust in your therapist. You also have to learn how to examine parts of yourself you’d much rather leave alone. It’s something Tony has never done before. He’s resistant. But when he mentions the ducks that took residence in his back garden, Dr Melfi detects something of significance.

“What was it about those ducks that meant so much to you?” she asks, gently persistent. Tony realises the truth: the ducks represent his own brood. “I’m afraid I’m going to lose my family,” he says, and bursts into tears. In that moment, The Sopranos proved itself to be a truly groundbreaking TV show, where Mafioso gangsters, so typically consigned to henchmen or comic relief status, now had emotional spaces of their own to occupy.

Not-so-tough guys can be funny

“If the wrong person finds out, I get a steel-jacketed antidepressant in the back of the head.”

Few shows have explored the Great Male Ego quite like The Sopranos. This was a show filled with thugs, bullies, lotharios and egomaniacs: guys all bound by the ironclad codes of masculinity that dictate life in the mob. Loyalty and honour are everything. To admit pain is to admit weakness.

Mafia life isn’t pretty. Legs are broken. Bullets are put in heads. But Dr Melfi’s description of Tony – “Sometimes, he’s just like a little boy” – could easily apply to the wider team of captains, soldiers and hardmen. Much like a gang of lads in the schoolyard, they jostle for status amongst themselves in displays of bravado borne of one thing: insecurity. Off-the-cuff jokes that are taken to heart. Poker games turn personal. No matter how brutal they are, you can’t help but often think, ‘Come on, guys – don’t be so thin-skinned!’

It’s insecurity that makes Tony so desperate to keep his sessions with Dr Melfi a secret. If stigma against seeking therapy is still pervasive today, it was way worse 20 years ago – not least amongst a group of alpha males in working-class New Jersey. It’s enough to threaten Tony’s credibility as mob captain. When Tony does finally reveal his secret to his crew, it’s met with a chorus of awkward mumbles. The clownish Paulie (played, always terrifyingly, by real-life former mobster Tony Sirico) admits that he himself saw a therapist, to “learn some coping skills”. What Paulie can’t get his head around is that Tony’s therapist is a woman. We’ll return to the subject of women in a bit.

Not-so-tough guys can be dangerous

So we know that the fragile egos of hardmen can make them very funny. But the fallout is anything but.

The entire arc of season one is structured around the struggle between Tony and his uncle, Corrado ‘Junior’ Soprano (Dominic Chianese) for top-dog position in the family. Both have something incriminating on the other – enough to destabilise the other’s position of authority. For Junior, it’s Tony’s therapy. For Tony, it’s that Junior likes going down on his girlfriend Bobbi, which, in mob circles, basically puts a guy at the level of a ‘finook’ (a derogatory term for a gay person). When the rest of the crew laughs at this, so do we: it’s a ridiculous thing to be so sensitive about. But when Junior discovers Bobbi has been indiscreet, his retribution is sadistic. This is what dented male pride can look like.

Similarly, when Dr Melfi probes Tony just a little too deeply about his mother in I Dream Of Jeannie Cusamano, he overturns the table in her office in a fit of rage and physically threatens her. Played with utter menace by the six-foot-one Gandolfini, we’re reminded this man is a brutal murderer. Even if he does cry about ducks in his backyard.

Then there are the desolate moments, like in Nobody Knows Anything in season one, when crooked cop Vin Makazian (played by the late, great John Heard) throws himself off a bridge after being caught at a brothel. It’s with a blank face that Vin silently decides on his fate: after a lifetime of sleaze and self-loathing, suicide is the only way out. Later, Tony discovers Vin suffered from depression. The Sopranos continually reminds us such of grim truths: that weak men are dangerous, and that unattended male mental health can have devastating consequences.

When it comes to mental health, men have lots to learn from women

“Psychology doesn’t address the soul… but (therapy) is a start.”

With the exception of the educated Dr Melfi, The Sopranos largely represented women in the subordinate roles typical of a fiercely traditional Italian-American community. Tony’s wife Carmela is a stay-at-home mother who spends her days at the gym or baking dishes for her priest and confidant, Father Phil. Tony’s mother Livia (Nancy Marchand), at the end of a similar life, rarely leaves her home and then nursing home. The crew’s ‘goomars’ (mistresses) are there for sexual entertainment. The strippers at nightclub Bada Bing, the mob’s legal front, cavort in the background as the guys talk business at the bar.

But that doesn’t mean there weren’t satisfyingly written, complex female characters in The Sopranos – women who, despite the domestic or ornamental roles, changed with the times far more than the men did. As Meadow Soprano (Jamie Lynn Sigler) dryly reminds her father, “This is the nineties” – a decade in which the self-help industry boomed, psychologists started to appear on chat shows, and therapeutic jargon started to enter public parlance. You get the sense that while the men of The Sopranos are out busting balls and screwing around, their wives are at home, self-diagnosing and teaching themselves about self-knowledge and emotional literacy.

This is definitely the case with Carmela Soprano, played with steely, layered brilliance by Edie Falco. Think of Carmela’s reaction when Tony admits he’s been seeing a therapist and is on antidepressants. “Oh my God,” she gasps, almost turned on. “I think that’s wonderful! That’s so gutsy!” Only when she discovers Dr Melfi is a woman does she voice any disapproval (though with Tony’s extramarital track record, you can hardly blame her).

For all her modern attitudes to therapy, Carmela remains a devout Catholic at heart, regularly seeking intimate council with parish priest Father Phil. Then, in the season one finale, she realises the quasi-romantic relationship that Father Phil enjoys with other mob wives, and that he’s on a power trip, even though he’s not aware of it. With the detached tone of a therapist, Carmela cuts short their friendship. “You have this M.O. where you manipulate spiritually thirsty women,” she tells the stunned priest. “Consider this an intervention.” Much loved by fans, the scene works in fabulous parallel to the relationship between Tony and Dr Melfi: even in the house of God, men need women for guidance.

Male mental health makes for amazing TV

“You know, douchebag, I realise I’m dreaming…”

Of its many accolades, one of The Sopranos‘ greatest achievements is the way it so used so many dream sequences as it did. It even introduced a character, the Italian dental student in ‘Isabella’, who turns out to be a figment of Tony’s libidinous imagination. By the standards of today’s television, which is as comfortable with surreality as the medium has ever been, some scenes do feel a little clunky. But when the dream stuff worked, it really worked.

Take The Test Dream in season five. With a good third of the episode taking place inside Tony’s head, the episode is of such staggering imagination and ambition and downright weirdness that you wonder how the writers got away with it. In dreams within dreams within dreams, Tony loses his teeth (we’ve all been there, right?), rides a horse, gets shot at by Lee Harvey Oswald, and meets Annette Bening (played by, yes, Annette Bening). It’s a bizarre tapestry of imagery and symbols that is still being picked apart by fans to this day. And remember, it’s all from the mind of a “fat fucking crook from New Jersey” (Tony’s words, not mine).

The Sopranos might be long concluded, with Tony leaving the office of Dr Melfi for the final time back in 2007. But that doesn’t mean the story has quite come to an end. A prequel film, The Many Saints Of Newark, is currently in production – and we should all breathe a major sigh of relief knowing that it’s being overseen by Chase. With James Gandolfini’s son Michael playing the young Tony, the film will be set during the Newark race riots of the 1960s, and focus on the preceding generation: Junior Soprano and Tony’s father, ‘Johnny Boy’ Soprano. More tough guys, more egos – and, no doubt, more mental health issues.