In 2006, screenwriters Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver were inspired by footage of domesticated chimpanzees who were unable to adjust to our lifestyles to write a sci-fi horror spec script that they called Genesis. Apparently, it was a while before the two of them realised that they were writing a Planet Of The Apes movie.

Their resultant pitch to 20th Century Fox led to 2011’s Rise Of The Planet Of The Apes, the excellent, emotional prequel/reboot of the franchise that led to 2014’s Dawn Of The Planet Of The Apes and recent trilogy topper, War For The Planet Of The Apes. Together, the three films take Caesar from domestication to domination and have been huge critical and financial hits for the studio.

The development hell that plagued Fox’s past attempts to expand the franchise must seem like a long way away now, but it’s fascinating to look back at what might have been, going all the way back to the beginning. The 1968 original was the result of a long period of development on adapting Pierre Boulle’s visionary novel La Planète Des Singes for the screen, but when it became a surprise hit, Fox soon asked producer Arthur P. Jacobs to come up with a sequel.

Jacobs requested and then turned down treatments from Boulle, who had no love for the first adaptation of his work, and Twilight Zone writer Rod Serling, whose work on the first film was rewritten for being too much like Boulle’s original socio-political satire. However, the 1970 film Beneath The Planet Of The Apes wound up borrowing a few ideas from each of their rejected treatments.

After the original series reached a circular conclusion in Battle For The Planet Of The Apes, the popularity of repeat marathons of the five films on US television got Fox interested in reinvigorating the franchise in the late 1980s, beginning a long and frustrating path to what would eventually become Tim Burton’s 2001 film, Planet Of The Apes, starring Mark Wahlberg, Tim Roth and Helena Bonham Carter.

For the following decade, filmmakers as varied as Oliver Stone, Peter Jackson and James Cameron all ran up against the studio’s difficult demands for the property and generated a number of potential scripts that ultimately went unproduced…

Return To The Planet Of The Apes

In 1988, Fox brought in Adam Rifkin to pitch ideas off the back of his little-seen debut film, Never On Tuesday. As a fan of Planet Of The Apes, Rifkin was interested in bringing it back, and was commissioned to write “an alternate sequel to the first film”, rather than a sixth instalment – the kind of idea that later reared its head when 2006’s Superman Returns is a sequel to the first two Christopher Reeve movies, and with Neill Blomkamp’s mooted sequel to Aliens.

Rifkin turned in Return To The Planet Of The Apes, which took place long after an ape civil war that put the gorilla, General Izan, in power and brought about ‘the Roman era’ of ape civilisation. A descendant of Charlton Heston’s Taylor, named Duke, (after John Wayne) would be the main character, who was raised by Cornelius (Roddy McDowall’s original character), and rose to defy the ape empire that killed Taylor through fighting in the arena.

Rifkin described his script as “a real sword-and-sandal spectacular, monkey style”, in David Hughes’ book Tales From Development Hell. “Gladiator did the same movie without the ape costumes. Having independent film experience, I promised I could write and direct a huge-looking film for a reasonable price and budget, like Aliens.”

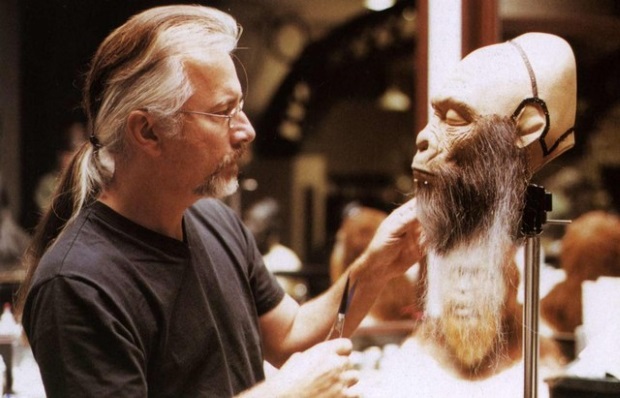

The script was in development for a while, and Tom Cruise and Charlie Sheen were considered for the lead role of Duke. Rifkin got as far as hiring Rick Baker to do the make-up effects (pictured above) and Danny Elfman to write the music – both would work on the eventual film that got made in 2001, but the writer-director would not.

As would happen several times over the course of this project, there was a changing of the guard at Fox, days before pre-production was due to begin, and Rifkin found himself mired in creative differences with the new studio executives. He performed several rewrites, but ultimately,he bristled at the studio’s demands for a happy ending and the project was abandoned.

Rifkin later told Hughes: “I can’t accurately describe in words the utter euphoria I felt knowing that I, Adam Rifkin, was going to be resurrecting the Planet of the Apes. It all seemed too good to be true. I soon found out it was.”

Peter Jackson’s ‘Renaissance’ Of The Planet Of The Apes

In 1992, Peter Jackson’s agent suggested that he pitch a new Planet Of The Apes movie, and the director immediately started work on a treatment with his screenwriting partner Fran Walsh. They pitched it to producer Harry J. Ufland, who was firm friends with Fox’s then-chairman, Joe Roth, and wheels started turning.

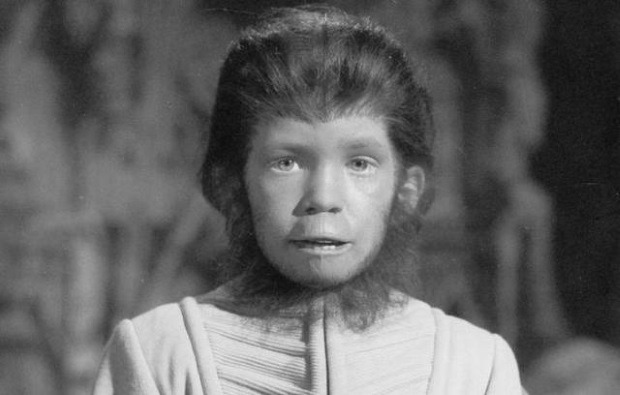

Their pitch wasn’t a reboot, but a sequel to the fifth film. Moving on from the Roman era parallels of Rifkin’s script, Jackson and Walsh moved forward to the Renaissance, the political unrest that was caused by the culture shock, and a potentially controversial hybrid creature that was excised from the first sequel, as detailed by Jackson in Brian Sibley’s book, Peter Jackson: A Film-maker’s Journey:

“We imagined their world being in the midst of an artistic renaissance, which made the ape government very nervous. […] The plot involved the humans rising in revolt and a half human, half ape central character that was sheltered by the liberal apes, but hunted down by the gorillas.”

This all sounds much more in line with the socio-political parallels of the original film. But in relation to the first film, a major coup was getting Roddy McDowall attached, after he had drawn a line under making any more Apes movies. They wanted him to play an elderly, Leonardo Da Vinci-inspired ape who would be the figurehead of the artistic movement. He loved the idea and was on board to return.

Roth supported the project too, but he left Fox in November 1992, and when Ufland and Jackson went to discuss the idea with head of production Tom Jacobson, their meeting went “incredibly badly” and left them under no more illusions that they had any allies left at the studio. To their horror, Jacobson didn’t even seem to know McDowall was ever in a Planet Of The Apes movie before.

Jackson and Walsh moved onto Heavenly Creatures instead, but would twice turn the project down after successive regimes at Fox invited him back. Finally, the duo would revisit another iconic monkey movie with 2005’s King Kong, and Jackson’s work on The Lord Of The Rings movies, with his effects house WETA Digital and actor Andy Serkis, would prove instrumental to the development of motion-capture technology used in the current cycle of the Apes franchise.

Oliver Stone’s Return Of The Apes

In late 1993, Fox met with Oliver Stone about Planet Of The Apes, at the urging of producer Don Murphy. At this meeting, Stone stood up and proclaimed that he had watched the original movies and hated them and then riffed a conspiracy thriller that rebooted the concept by integrating a Stone Age ape society, time travel and numeric codes in the Bible which predict the end of civilisation.

We swear to Caesar we are not making this up, but Stone did make it up, and Fox gave him $1 million to produce and co-write the film. Still, the goal was to make a massive four quadrant blockbuster.

Murphy told Sci Fi Universe in 1994: “We are not making the reinvented Planet Of The Apes to appeal to the hundred or thousand people who cannot get enough of the Apes marathons once a year when some channel like TNT runs them.

“We’re going to make it so it appeals to forty million people who want to see what could easily be the next Jurassic Park… it’s going to be Gorillas In The Mist meets The Terminator – a humungous rethinking of the entire concept.”

Terry Hayes, who wrote the Mad Max sequels, was behind that rethinking and turned in a draft called Return Of The Apes. In a 21st century prologue, we learn that geneticists Will Robinson and Billie Rae Diamond are trying to find out why babies are growing old and dying in the womb, as part of a larger pandemic of accelerated ageing that has wiped out most of the human race.

Discovering that it’s down to a flaw in human DNA, they go on a one-way trip back in time (using their own DNA, years before Assassin’s Creed delved into that sort of thing) to discover the reasons why, and find out that in the Stone Age, apes battle humans for dominance of the planet. Together, they try to save the future and in a bittersweet ending, Diamond delivers a healthy baby while Robertson builds a Stone Age Statue of Liberty as a monument to where they came from.

The aim was for a mythic, steampunk take on the premise, marrying elements of Biblical lore and Tolkien in a prehistoric setting. In the latter regard, Hayes’ script features numerous brazen lifts from The Lord Of The Rings, including several characters named Aragorn, Strider and Nazgul. Ironically, this was a few years before Jackson would make all of these names a lot more well known.

The script had more of an action-adventure bent than previous attempts, in an attempt to increase its appeal. In line with their stated influence from The Terminator, Arnold Schwarzenegger was signed up to play Robinson (in between his other super-convincing turns as scientists in 1994’s Junior and 1997’s Batman & Robin), and the mighty Stan Winston was hired to design the effects and prosthetic make-up. Early in 1995, Schwarzenegger approved Phillip Noyce to direct and the film was ready to proceed with a $100 million budget.

But at this point in active development, Fox executives weren’t seeing eye to eye with the producers and in particular, the studio’s new head of production Dylan Sellers had some strange ideas about how to add more humour to the dense and mythic script in rewrites.

As producer Jane Hamsher tells it, Sanders said: “What if Robinson finds himself in Ape land and the Apes are trying to play baseball? But they’re missing one element, like the pitcher or something… Robinson knows what they’re missing and he shows them, and they all start playing.”

The creatives were staunchly against this idea and Sanders wouldn’t give it up. After the next draft came in sans baseball, Hayes was fired, Murphy and Hamsher were taken off the project and Stone and Noyce both turned their attention to other projects. Only Schwarzenegger remained attached, and cinema wouldn’t get its ape baseball movie until 2013, in Korean 3D sports comedy Mr. Go.

Chris Columbus and Sam Hamm

Murphy would later lament that “Terry wrote a Terminator and Fox wanted The Flintstones”, referring to the kitschy Spielberg-produced live action reboot that had been a success for Universal a few years earlier. That could explain why Fox’s next hire for the project was Chris Columbus, who had written Home Alone and directed Mrs. Doubtfire for them in recent years.

Columbus roped in screenwriter Sam Hamm, with whom he had collaborated on an unproduced Fantastic Four project around the same time. Hamm wrote a script that took elements from the much bally-hooed Hayes script (particularly the ageing virus), but also went back to Boulle’s novel for inspiration and added a female lead, Dr. Susan Landis.

The film would have started in contemporary New York, with a spacecraft crash-landing in the Manhattan harbour. Inside is an ape astronaut, who is killed by frightened guardsman, inadvertently unleashing the virus. A team including Landis and Dr. Alexander Troy (presumably Schwarzenegger’s character, who reprises the famous “damn dirty ape” line later on) repairs the craft, travels to the ape’s planet of origin looking for an antidote.

Instead, they find a militarised society of primates hunting humans in an urban environment, ruled by the cruel Lord Zaius. However dark that sounds, it seems like Fox still got their wish in terms of getting Flintstones-style humour, with Hamm’s kid-friendly script having various references to human pop culture, including “an ape cover of Stayin’ Alive by the Bee Gees” and one ape leafing through a simian version of Playboy magazine.

The script ended in a homage to both the novel and the original, with Dr. Troy arriving back in Manhattan with a viable cure to the virus, only to find that due to time dilation throughout his travels, the ape takeover has happened in his long absence, with the Statue of Liberty getting a grinning monkey makeover.

The notorious leftfield ending to Burton’s film might well have been a hangover from this draft, or an independent desire to draw influence from the novel as well, but either way, this one was a mashup of all of the development thus far. Columbus moved on later in the same year, and produced Jingle All The Way with Schwarzenegger and Flintstones director Brian Levant instead.

James Cameron

The next filmmaker that Fox approached was none other than James Cameron, who had already passed before Columbus came on board and was then busy filming Titanic. This time, he agreed to produce the film, with Schwarzenegger starring and someone else directing.

In 1996, Jackson and Walsh re-pitched their original screenplay to Fox executives and Jackson was offered the director’s job. This time, he turned it down, having been burned by the studio before and fearing the possibility of creative differences with a famously hands-on producer and star.

Cameron reportedly wrote a script after Titanic was done and dusted, in which he went back to Rifkin’s notion of making an alternate sequel to the original, starting the movie with the crash of Taylor’s ship from the beginning of the 1968 film and then flashing forward to more astronauts arriving years afterwards. An unverified leak suggested that the film would have five new characters crash-landing and teaming up with Taylor (still played by Charlton Heston) to fight a Caligula-like ape prime minister.

By 1998, Cameron had convinced an initially sceptical Peter Hyams (whose sci-fi credentials included Capricorn One and TimeCop) to direct by showing him 10 minutes of footage from Stan Winston’s make-up tests.

Hyams recalled to Daily Dead in 2014: “It was absolute perfection; I couldn’t believe that Stan actually cracked it. I even asked Stan about how he managed to pull it off but he wouldn’t tell me- I just remember thinking it was absolutely stunning work and it was a real shame that fans never got to see Stan’s vision for these apes come to life.”

Unfortunately, Fox fired Hyams before production and a disillusioned Cameron cleaned his hands of the project. Schwarzenegger left with him. After that, Roland Emmerich, Michael Bay and the Hughes brothers all rejected offers from Fox.

Finally, Jackson turned down the project yet again in 1998 when The Lord Of The Rings hit a roadblock, because he had lost enthusiasm for his original script after the recent death of McDowall, who had remarked upon the state of the franchise soon before his passing.

In his final interview, he told TV Guide Online: “I don’t see any reason to remake them. Why? They’re there and they’re as potent as ever. On the other hand, I’ve always thought it would be very sensible to continue the canon and I can’t imagine why nobody’s done so.”

Conclusion: It was Fox all along…

Judging by the evidence, it was because of a heck of a lot of creative meddling by the studio. From there, Fox turned the project to producer Richard D. Zanuck, who had greenlit the original Apes movie back in the day, and hired Tim Burton to direct a ‘re-imagining’ of the franchise. Creative meddling continued throughout the shoot, demanding rewrites and insisting upon the projected July 2001 release date.

The inevitable result of all of this was a huge financial hit that ended in a cliffhanger but never got a sequel, because the higher-ups at Fox were so put off by the vitriolic reaction from critics and audiences. And also because a bruised Burton said he’d “rather jump out a window” than make a follow-up.

We’re sorry that there’s no trademark twist ending to all of this, but it turns out that when you’re a studio executive who can’t take your damn dirty hands off a sequel/reboot/re-imagining that’s been pushed one way or another for more than a decade, you might have been the problem all along.