Warning: contains seasons 1-7 spoilers.

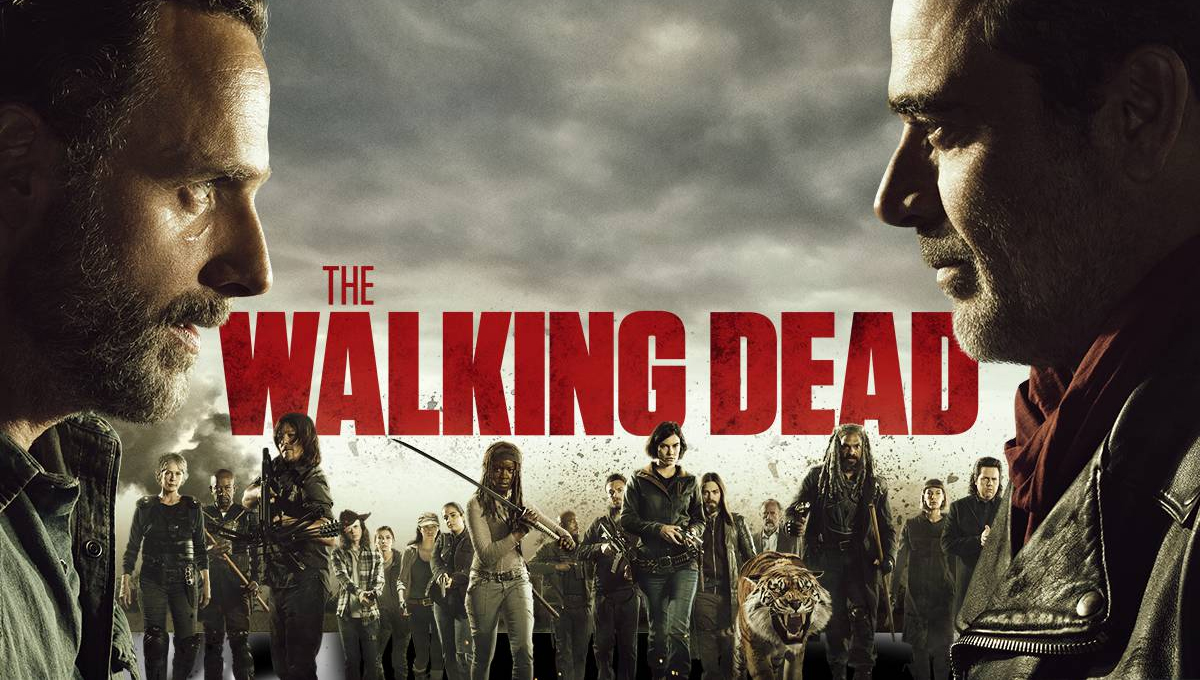

As we prepare for an imminent return to the post-apocalyptic, pre-war, pro-tiger world of The Walking Dead, this feels like the perfect time to evaluate the leadership skills (or lack of them) of the show’s main protagonist and antagonist: watery-eyed psycho-sheriff Rick Grimes, and the bonce-bashing batsman y’all like to call Negan, but whose real name is probably Graham or something. Are these two guys effective leaders? Worthy leaders? Great leaders? And, more to the point, should either of them have survived this long into the zombie apocalypse?

Let’s start with Rick: Rick is a great leader. We know this because all of the other characters in the show repeatedly tell him that he’s a great leader; when they aren’t telling him directly, they’re discussing it amongst themselves. In fact, Rick’s greatness is the number one topic of conversation among regular, every-day Alexandrians, second only to how much they’d like to eviscerate Carl (partly as an experiment to see if losing his internal organs like a string of errant sausages would finally make the surly little chap emote about something. But mostly just because he’s Carl).

If talking about Rick’s greatness is akin to prayer for the people of Alexandria, then it follows that disagreeing with his greatness is nothing short of blasphemy. Any minor character stupid enough to question Rick’s infallibility as leader, or disagree with his tactics in any way, will always find themselves facing death in a tremendously brutal and unfair way.

“Rick got my entire family killed yesterday, because he woke up angry after a dream and decided to dynamite half the town. The guy’s a dick.”

“You don’t think he’s great then?”

“Well… no.”

“Are you sure about that, Guy Whose Name We Don’t Know Yet?”

“Of course I’m bloody sure.”

Points up to the heavens, and talks in a whisper. “But are you really sure?”

Nods. “Yeah. Rick’s an asshole.”

Guy Whose Name We Don’t Know Yet sneezes and propels himself backwards into a pit of hungry zombies, who proceed to feast upon his head. On his death certificate the town doctor scrawls: ‘Death by writer,’ and then she gets killed too, because she once criticised Rick’s shoes.

Despite the pre-mortem tuts of his in-universe critics, a broken clock – or a broken Rick if you prefer – is still right twice a day. Rick’s madness-tipped brutality has helped extricate the gang from peril on many occasions, from his plan to ambush and lacerate a gang of cannibals to death in Gabriel’s church, to his (admittedly rather instinctual) plan to bite out a baddy’s throat to save Carl from a rapist: sometimes crazy pays. Indeed, a degree of fiery recklessness and devil-may-care jack-bootery is probably essential if you want to make a habit of surviving beyond the pre-credits sequence.

But for every positive application of Rick’s trademark craziness there are a hundred instances of him taking an already bad situation and making it not just worse, but Fear The Walking Dead worse. His lunacy tends to be responsible for the deaths of more innocent people than Gwyneth Paltrow’s unwashed hands in Contagion.

This is the man who led thousands of zombies past his vulnerable settlement like some sort of demented Pied Piper of the Biters. And when things went wrong and his town became over-run with Walkers, he didn’t formulate a strategy to thin out their numbers or divert them elsewhere again. No. He spent an entire evening beating thousands of them to second-death with his bare hands. Inexplicably, his subjects joined him. Now that’s what I call a proper team-building session, Rick: paint-balling is for pussies.

Rick tried to solve his Negan problem by begging for an alliance with a bunch of slack-jawed, de-evolved junkyard people who had inexplicably lost the ability to speak English after only eighteen short months. When they based his worthiness to receive aid upon how well he did fighting their pet zombie in a trash-pit rumble, Rick just thought to himself, ‘If I’ve any minor complaint, it’s that these guys seem way too normal. I’m absolutely convinced that they aren’t wrong in the head, and I’d be completely shocked if they ended up double-crossing me somewhere down the line.’

Most of Rick’s actions since season three have only served to vindicate Shane’s assessment of his leadership skills way back in season two. Even when Rick manages to carry out a plan that looks Shane-worthy on paper, it’s a plan capable of bringing even Shane to shame; like rigging explosives around a group of traumatised women and children in order to steal their guns, leaving them vulnerable to the very people they’d armed themselves against in the first place. Gee thanks, Rick. You’re the best. Are you sure your surname isn’t Sanchez?

In marked contrast, Comic-Rick is a genuinely great leader. Like his TV counterpart, he’s no stranger to episodic madness or dangerous levels of hubris, but in general he’s a pragmatic, forward-thinking strategist with just enough compassion to keep him the right side of human, and just enough bad-assery to make the wrong ‘uns think twice about messing with him. When Comic-Negan came-a-knocking at Alexandria following Glenn’s midnight eye-ectomy, Rick only pretended to play the part of snivelling supplicant; in reality he had already formulated a daring, cunning plan to fight back, which he initially kept secret from all but his most trusted lieutenants. When TV-Negan (or TVegan, if you like) came-a-knocking at Alexandria, TV Rick didn’t just pretend to be a snivelling supplicant: he became one.

Comic-Rick has balls. The denizens of the apocalypse are lucky to have him in charge. I can easily imagine him sitting in a disused air hangar reading zombie fairy tales to his grandchildren long into the future. TV Rick, on the other hand, has a severe personality disorder caused by haphazard writing, and I’m surprised he survived past Hershel’s farm. In the real world, I wouldn’t put him in charge of a church fete. I’d be too frightened he’d snap and start mowing down old ladies with his car, or somehow unleashing a horde of crocodiles on the screaming guests. Rick Grimes is Ophelia meets Forrest Gump meets Tackleberry meets Michael Douglas in Falling Down. If I lived in a community in which there was a realistic chance he might become head honcho, I’d be over the fence and running before you could say, ‘Well hello Mr Pee Pee Pants.’

Speaking of which, let’s leave Rick’s woeful leadership legacy to one side and pay a visit to the ‘baddy’ camp.

Ah, Negan. I get that he’s supposed to be both a ruthless pragmatist, and an unhinged narcissist. It’s just that, in practice, his narcissism, and especially his creepy predilection for love through complete psychological domination, isn’t exactly the stuff of which inspirational leadership seminars are made. If you capture someone whose every atom is screaming out to brutally murder you, it’s probably not a smart use of your time, or a great way to insulate yourself from harm, to attempt to bring them to heel like they’re an abused dog.

In the comics, Negan is a hulked-up Henry Rollins, a rabid Tony Soprano for the apocalypse. I don’t know exactly how he rose to become the most powerful dictator in all of Washington, but given his imposing physicality and flair for casual brutality I have no difficulty in imagining him asserting himself as the alpha of a small band of madmen and working his way up from there.

TV Negan, on the other hand, is like some smarmy asshole from an exclusive golf resort, giving you a hard time because both your car and your wife are much older than his. I can’t picture his ascendancy to the position of invincible warrior-prophet. I can’t picture him winning a fight without a platoon of goons having his back. His neck already looks broken, for Christ’s sake, or it soon will be if he keeps doing that weird drunken tap-dance every time he speaks. I’m genuinely surprised – to the point where it begins to stretch credibility – that one of the maniacs under Negan’s tenuous command hasn’t violently assassinated him.

When Negan raises his voice to shout, employing his weirdly over-emphasised, Shatner-esque shtick, it’s not a mercurial, megalomaniacal, homicidal demigod that’s brought to mind, but a hitherto mild-mannered deputy head teacher losing his shit at the school assembly. TVegan is a smug, sleazy, cheeky asshole, who just happens to have insinuated himself into a position of supreme authority while everyone was looking the other way. Not only does he not feel like a real and credible threat, he doesn’t even feel like a real guy; just a composite of hammy panto villains, a wicked step-mother that occasionally gets to stove people’s heads in with a baseball bat. Most of the time he just talks, and talks, and talks, and talks some more, blathering on about peed pants like some octogenarian rock star slowly rotting away in a nursing home.

I can understand why Comic-Negan let Comic-Carl live; why he was so effusive about the boy; how he praised him for having balls the size of steroidal asteroids: because Comic-Carl was a boy. An actual boy. If you witnessed a six-year-old proving his killing skills with an automatic rifle, you might be suitably impressed, too. If a whiny emo-teen with lank hair and an eye-patch tried and failed to murder you, you’d probably just shoot him dead on the spot right there and then.

In fairness, that contrast isn’t the fault of the TV show. Since the comics are unencumbered by the unavoidable aging and decay that comes with having a cast of 3D human actors, Comic-Carl didn’t have to visibly age five-or-six years over the course of a six-month chunk of storyline. That being said, the decision to include that plot-line from the source material made Negan look needlessly indulgent and ineffective.

Negan may not be a terribly good leader, but he’s a pretty effective allegory, if looked at from a certain direction. Far from imagining himself to be the villain, Negan actually thinks he’s the good guy. The Saviors – Negan’s ruthless, heavily armed group – gets rich on the back of less developed or less equipped communities. Negan turns all strangers he encounters into slaves, putting them to work foraging for food, amenities and luxury goods on his community’s behalf, always in squalid and dangerous conditions, and for almost nothing in the way of recompense.

Indeed, the only ‘reward’ that these communities ‘enjoy’ is the mild advantage that comes from Negan’s group clearing the area of zombies – in The Saviors’ capacity, of course, as the region’s self-appointed policemen and hegemonic super-power.

The Saviors are America. And I suppose that makes Negan… Trump? I’m sure even Negan would be appalled by the comparison.

I for one think that there’s something delicious and mischievous in the idea that by cheering for Negan’s comeuppance, we Brits and Americans areactually secretly cheering for our own violent downfall.

Whichever one of our two big-league leaders wins the great war to come – and I think we all have a sneaking suspicion which leader that will be – there’s no denying that the thought of them going toe-to-toe – or hat-to-bat if you like – for an entire season is generating levels of excitement and anticipation not felt since we first saw the prison looming over the ashes of Hershel’s Farm.

Let’s hope it’s a dirty fight.

The Walking Dead season 8 starts on Sunday the 22nd of October on AMC in the US and on Monday the 23rd of October on Fox here in the UK.